Here is a tutorial and documentation on measurements I perform. I will update it from time to time to keep it current.

Equipment

The weapon of choice for me is the Audio Precision Sys-2522. Here is a picture of it in my rack (top box):

This is a very capable device able to work both in digital and analog domains. I can for example use the analog output in both balanced and unbalanced configuration to drive an amplifier, and measure its output again using either balanced or unbalanced inputs. In addition, it has digital output capable of generating both AES/EBU balanced and S/PDIF plus Toslink optical. All of these ports can be programmed to create jitter on demand to test robustness and fidelity of digital input on both consumer and professional equipment.

Retail price originally was around $25,000 which in today's prices is probably $40K. The box is rather old though and discontinued. Fear not. It is still exceptionally capable due to user interface and some of the processing being connected to a PC over USB. As such, it still operates like a workhorse. An ex-salesman for Audio Precision (AP) said in an online review that their biggest competition was ebay (i.e. used Audio Precisions)!

A bit of background on AP, Tektronix and HP used to own audio instrumentation (besides other domains). Their boxes were expensive but highly limited. A bunch of Tektronix engineers left and started Audio Precision where the UI functionality was in the PC as mentioned above. And the device was fully capable including such things as stereo measurements which the Tek/HP gear lacked. I heard about them when I was running engineering at Sony in early 1990s. Was almost going to buy an HP unit until I heard about AP. Could not believe how much better it was. So purchased the unit and found out no one in Sony Japan knew about it either.

The unit is no longer in calibration and I am in no mood to spent big bucks getting it calibrate. Such gear drifts very little and at any rate, you should be looking at measurements in relative mode and order magnitude. As an example if a distortion spike is at -130 graph, it could be a dB up or down. That doesn't matter to the type of analysis we are doing.

By the way, John Atkinson at Stereophile performs all of his measurements using almost as old a unit as mine (the AP 2700: see: https://www.stereophile.com/asweseeit/108awsi). I am pretty sure his is not calibrated recently either. So I am good company.

AP has upgraded their gear but all of their new units sans one underperform my analyzer! The only one that does better is the APX-555 series that retails for $28,000. One day I might upgrade to that but the difference in performance is not worth it right now. My analyzer is able to go deeper than threshold of hearing on many measurements.

Audio Precision and Rhode and Schwartz dominate the high-end of audio measurement field and demand high prices for them. You can buy cheaper units such as Prism Sound dSound which I have also used but you lose some performance in the front-end.

Theory of Operation

At high level, the Audio Precision is nothing more than an analog to digital converter. Input signals are digitized and then analyzed and reported as graphs. So in theory you could use a sound card to do the same thing. The big difference is that the AP is a known quantity so results can be replicated by others whereas sound card come in so many variations that comparing their results gets hard.

Another huge difference is the analog scalar front-end in AP. The controller in the analyzer is constantly monitoring input levels and scales them to the most ideal range for its ADC. This allows the internal ADC to work at its most linear and optimized level. In addition, the same logic allows measurements of high voltage inputs up to something like 150 volts! This is necessary for measurements of amplifier that can output such high voltages. If you connected an amp to a sound card input it would blow it up in an instant.

Signal Processing

Some of you may be wondering about a catch-22 issue: how can an older analog to digital converter keep up with the latest in digital to analog conversion? Wouldn't the noise from the old ADC dominate? The answer is no. Using signal processing we can achieve incredible amount of noise reduction. This occurs when we use the Fourier Transform ("FFT") to convert time domain signals to frequency. By using many audio samples, we are able to gain in the order of 32 db or so in noise reduction (called "FFT gain"). This allows us to dig deep to as low as -150 db looking for distortion products. This floor is well in excess of hearing dynamic range (around -116 dB).

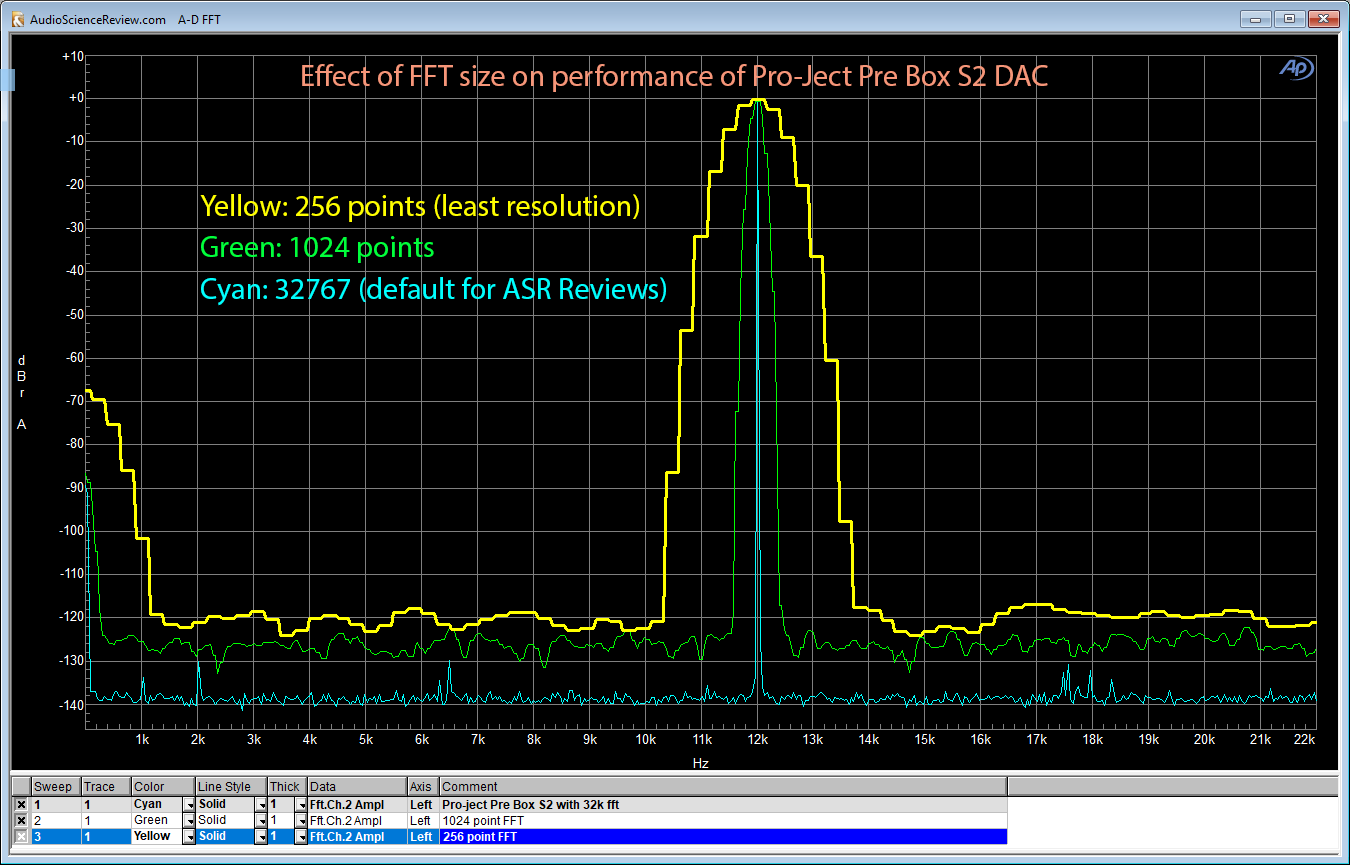

Unfortunately this FFT gain is source of a lot of confusion. By increasing or decreasing the FFT gain, we can make the noise floor of a DAC better or worse on demand. Without compensation, graphs using different FFT sizes cannot be compared. I use 32K FFT which is a great balance between noise reduction and not having too much detail that is hard to interpret. I have seen measurements using 2 million point FFTs which produce extremely low measured noise floors that can mislead one quite well.

In addition averaging can be used to reduce variations in noise floor. Combined, these two techniques perform miracles in allowing is to measure analog output of equipment to incredible resolution.

The bottom line in cyan is the 32K FFT I use in all of my measurements unless noted otherwise. Notice how it has lowered the noise floor much more than the 256/1024 points. But importantly the noise floor is so low that we now see spikes that are 130 dB below our main tone at 12 kHz!!! The noise floor itself is at -140 dB which is way better than either the DAC or ADC can do (approaching 24 bits) let alone the combination of both. Such is the power of software and signal processing. Once in a while we get a free lunch.

Test Configuration

For above test, I ran the digital output from AP using a BNC to RCA adapter to a 3 foot coax cable which then connected to S/PDIF input of Pro-Ject. This is the same as you using a transport or USB to S/PDIF converter except that my analyzer is the source. Inside AP I can set the sampling rate and bit depth. The default for the J-test above is 24 bit, 48 kHz. I sometimes run 44.1 kHz. I am using 48 kHz because sometimes DACs are only optimized for 44.1 kHz and not 48 kHz (and multiples thereof).

The output of the DAC is unbalanced RCA which I connect back using a 6 foot or so, monster cable interconnects I have had for a couple of decades. It is a beefy cable with pretty tight RCA terminations.

Sometimes I test the balanced output of equipment. In that case I usually use a set of balanced cables I purchased from Audio Precision. They are kind of thin but very short so fine for testing.

For other tests like headphones I use either adapters from 3.5 mm/TRS to RCA or cables with those terminations on them. So nothing fancy here.

PC Testing

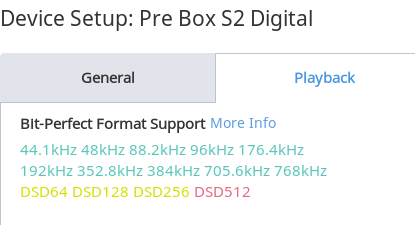

Toda many of us use external DACs with our computers using USB. For this reason I have converted some of my tests so that the source is generated by the computer but then captured and analyzed by the AP. For that, I use my normal everyday music player, Roon. In almost all cases I allow Windows 10 to detect the sound card and "gen up" the WASAPI interface which I use in exclusive, "bit-exact" mode. I usually capture the output of Roon format detection in my reviews. Here is the output for example for Pro-Ject Pre Box S2 Digital:

Roon has a nice indicator for when it is playing the file exactly or is converting it which is useful.

I used to use Foobar2000 which you may see in my older reviews to same effect.

Note that if Windows detects the device as is the case here, that is what I test. I only install drivers if I have to which thankfully these days is rare.

The computer I use for testing is my everyday laptop running Windows 10. It is an HP Z series "workstation." I am usually running other things on it while testing. No good DAC cares about that although some rare ones do (e.g. Schiit Modi 2). I have a Mac but have not done any work on it.

Tests

I will focus on DAC testing here which is most of what I do. Over time I will add to it for testing of other products.

j-Test for Jitter and Noise

My starter test is always the so called "J-Test." This is a special test which was developed by the late Julian Dunn which is the most recognized authority when it comes to standardizations and issues around serial digital audio transmission (i.e. AES/EBU and S/PDIF). He developed the J-Test signal as a way to increase amount of jitter which may be induced with the cable. And at the same time, it is a signal that is pure it its own.

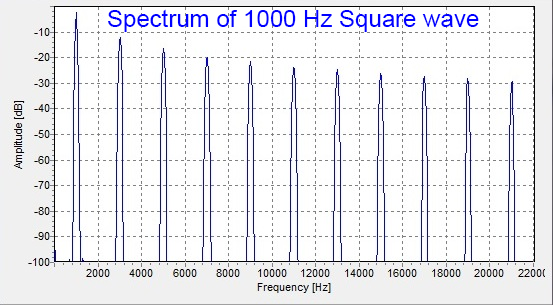

J-Test is comprised of a square wave at 1/4 the frequency of the sampling rate. In the case of my default testing, sampling rate is 48 kHz so that square wave will become 12 kHz. Very oddly what comes out of the DAC is not a square wave but a sine wave! Why? Because to make a square wave you make a sine wave and then add to it infinite series of odd harmonics. The third harmonic will be the first addition at three times 12 kHz or 36 kHz. Because our sampling rate is 48 kHz, the DAC will filter out everything at half of that frequency or 24 kHz. Therefore none of the harmonics of that square wave get out. The only thing remaining is the first component which is a 12 kHz sine wave!!!

Why do we use a square wave as opposed to a 12 kHz sine wave? Well to create a sine wave we need to use fractional numbers. Digital audio samples on the other hand are all integers. We can convert those fractions to integers but we then must use some amount of noise as "dither" otherwise we create distortions. That raises the measured noise floor which is not good. Square wave on the other hand is just high or low numbers at fixed PCM values so we have no rounding/dither/noise to to add or worry about.

In addition to above, the J-Test signal varies with a fixed frequency to the tune of one bit. That one bit is designed to force all the bits to flip. Even though the level hardly changes, the effect on the cable and the receiver is significant. Normally this flipping bit will be visible in spectrum analysis when performing the test in 24 bits as I do. However, you never see it in my test since my FFT is not large enough to make it visible (you do see it in JA's stereophile tests). So from practical point of view, you can ignore everything I said in this paragraph.

The measurement you see posted above is the J-Test. We have our single peak in the middle representing the 12 kHz tone. Everything on the sides in an ideal DAC would be an infinitely low noise floor. Real DACs have higher noise floor and spikes here and there. If spikes are symmetrical around our main tone, they usually mean there is "jitter." Other spikes can exist by themselves indicating idle tones created due to interference or other problems in the DAC. In other words, the quieter the space around our 12 kHz peak, the better.

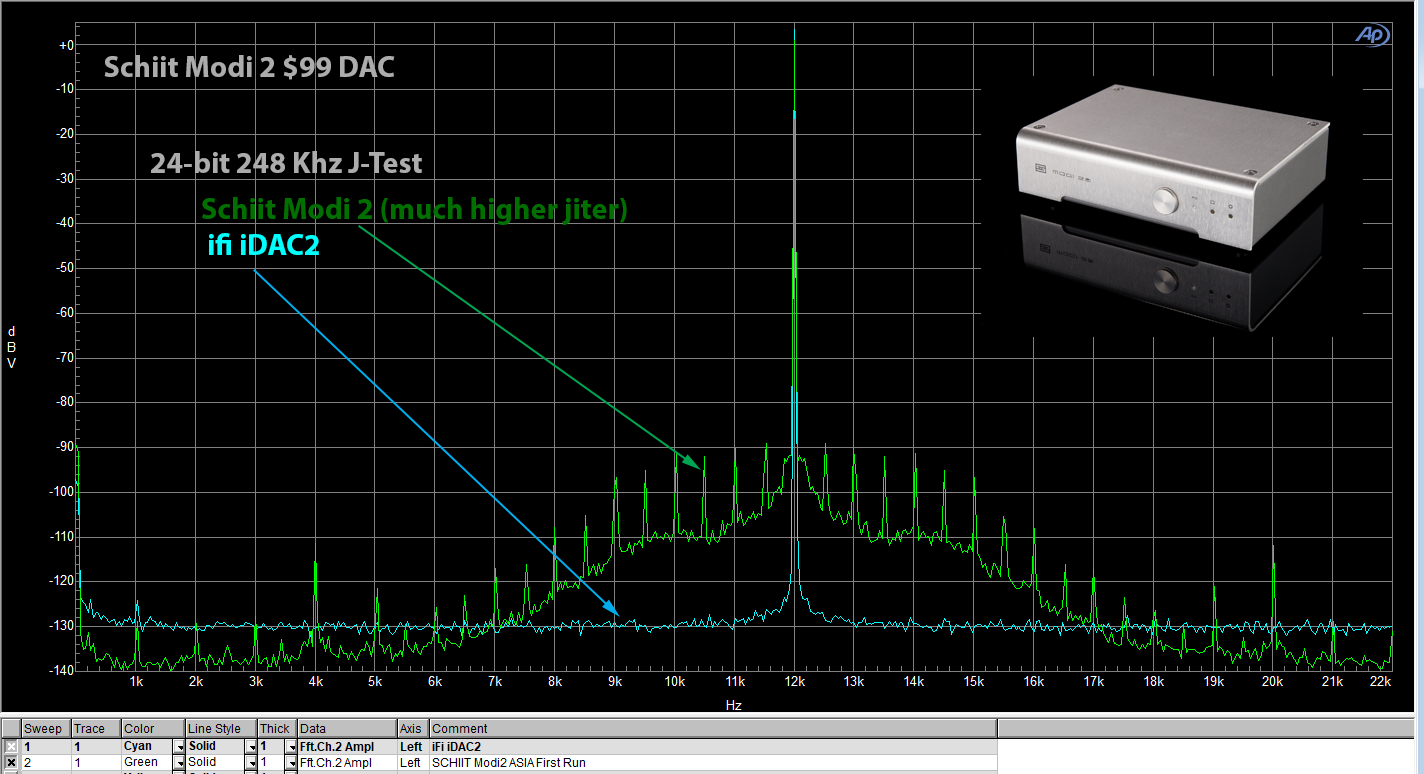

I usually show two devices on the same graph so that the contrast is easy to see. Here is an example from review of Schiit Modi 2:

As we see the iFi iDAC2 is much much cleaner than Schiit Modi 2. It has a flat, smooth noise floor whereas the Schiit Modi 2 has a bunch of distortion spikes (deterministic jitter) in addition to raised noise floor around our main 12 kHz tone (low frequency random jitter). The iFi iDAC2 is clearly superior.

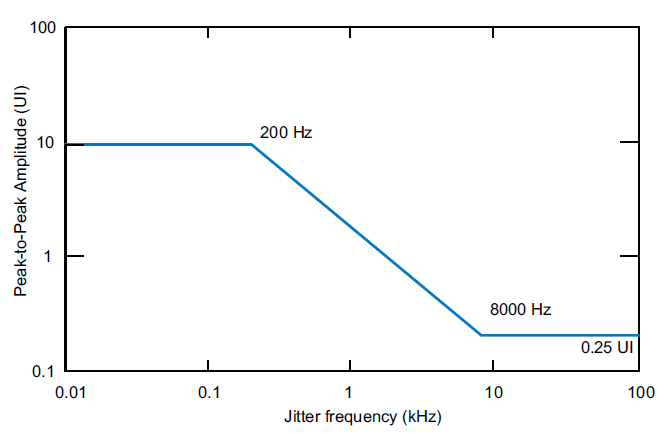

Note that due to a psychoacoustics principle, jitter components hugging our main tone of 12 kHz are much less audible than the ones farther out from it. That distance is the jitter frequency. We can put this in the form of a graph as done by Julian Dunn:

Note: there is no jitter in the test signal itself. It is the nature of a higher frequency tone like 12 kHz to accentuate jitter because jitter correlates with how fast our signal is. Small clock differences don't matter to a slow low frequency wave like 60 Hz. But make it 12,000 Hz and small variations in clock to produce the next sample can become a much bigger deal.

It is said that J-Test is useless for non-S/PDIF interface. This is not so. Yes the bit toggling part was originally designed for AES/EBU and S/PDIF but the same toggling causes changes inside the DAC which can produce distortion/jitter/noise. And per above its 12 kHz tone is revealing just the same of jitter.

Here is Julian Dunn in his excellent write-up for Audio Precision on this topic:

While the above talks about AES/EBU balanced digital interface, the same is true of S/PDIF.

Linearity Test

I run this test using the AP as the digital generator because it needs to be in control of changing the level. It produces a tone which it then makes smaller and smaller and compares the analog output to expected one from the digital samples:

I usually create a marker where the variation is around 0.1 dB of error. I then look up its amplitude (-112 dB above). I divide that by 6 and get what is called ENOB: effective number of bits. This gives you some idea of how accurate the DAC is in units of bits. Above we are getting about 18 bits.

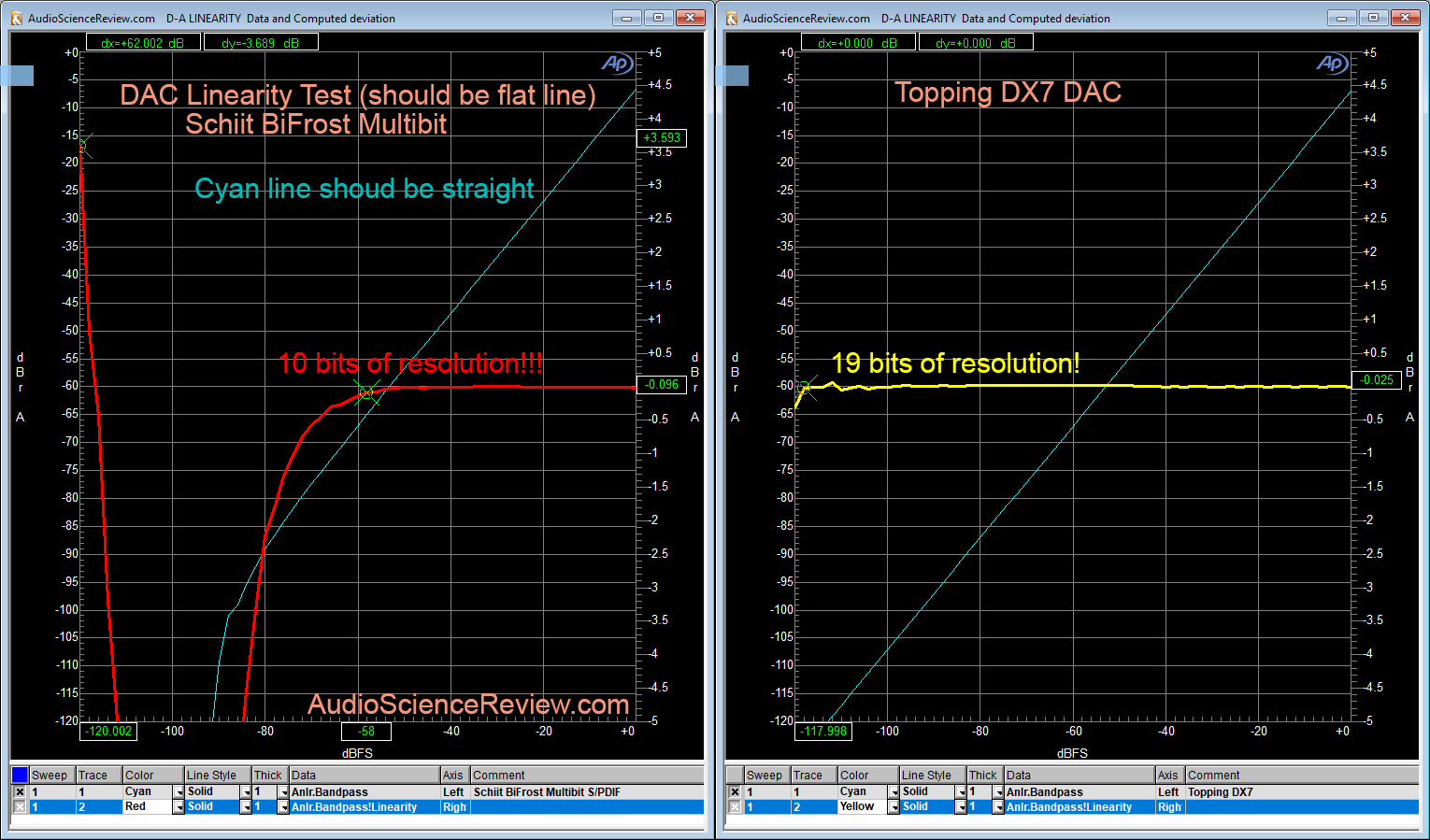

Here is an example of a bad performing DAC, the Schiit BiFrost Multibit:

In an ideal situation we would have linearity going to 20+ bits. Reason for that is that in mid-frequencies absolute audible transparency would require about 120 db which is 20 bits * 6. As a lower threshold I like to see at least 16 bits of clean reproduction. No reason we can't play CDs/CD rips at 16 bits with any error after so many years since the introduction of that format.

Linearity Test Take 2

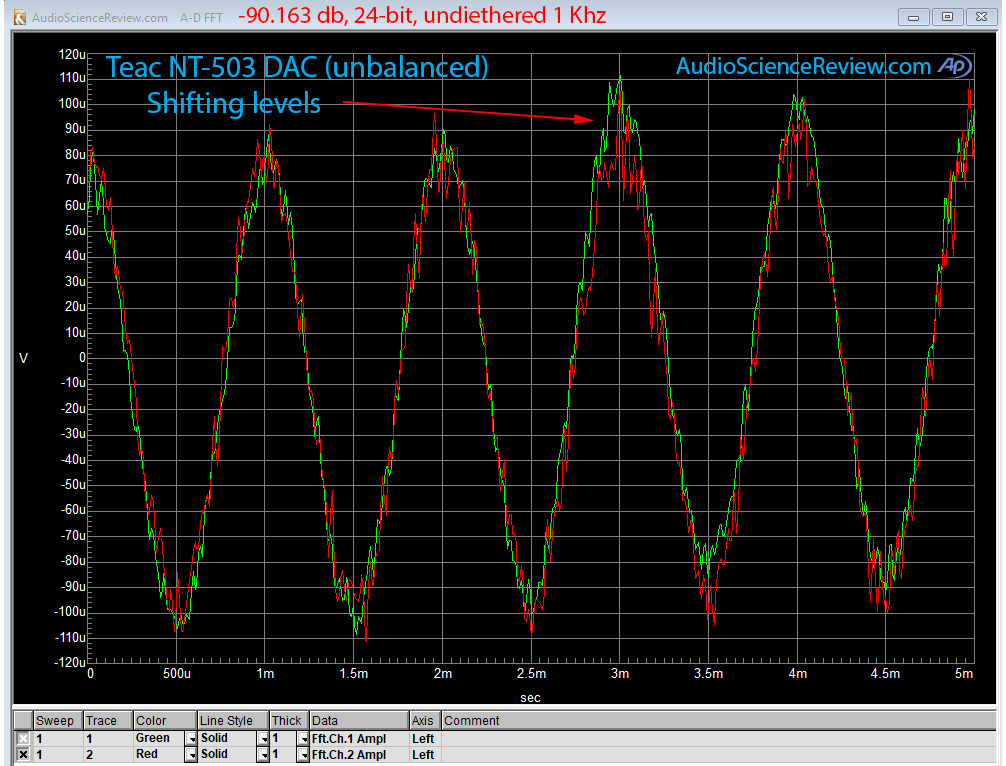

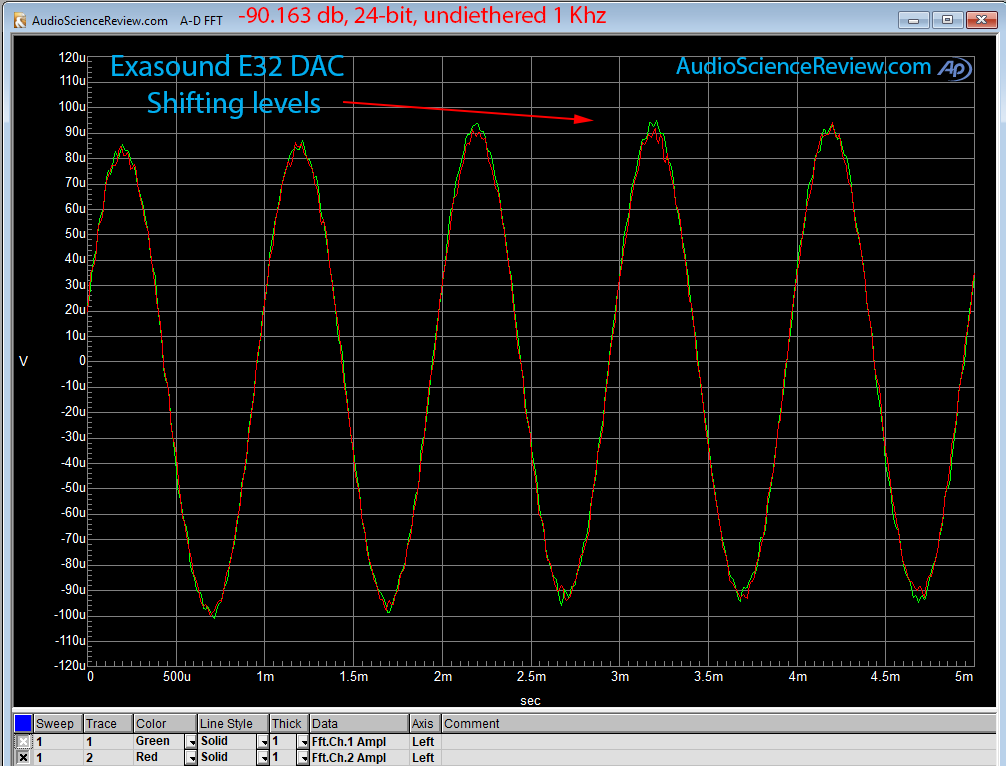

Another way to look at linearity is to see how a very small amplitude sine wave at just -90 dB can be reproduced using 24-bit samples and no dither. Put more simply we want to see if the rightmost bits in a 16-bit audio samples can be reproduced cleanly. If so, we should see a perfect sine wave. Here are two examples, first the Teac NT-503 and then Exasound E32:

The beauty of this measurement is that we can visually confirm accuracy. Any noise or incorrect conversion of digital to analog causes the waveform to deviate from ideal.

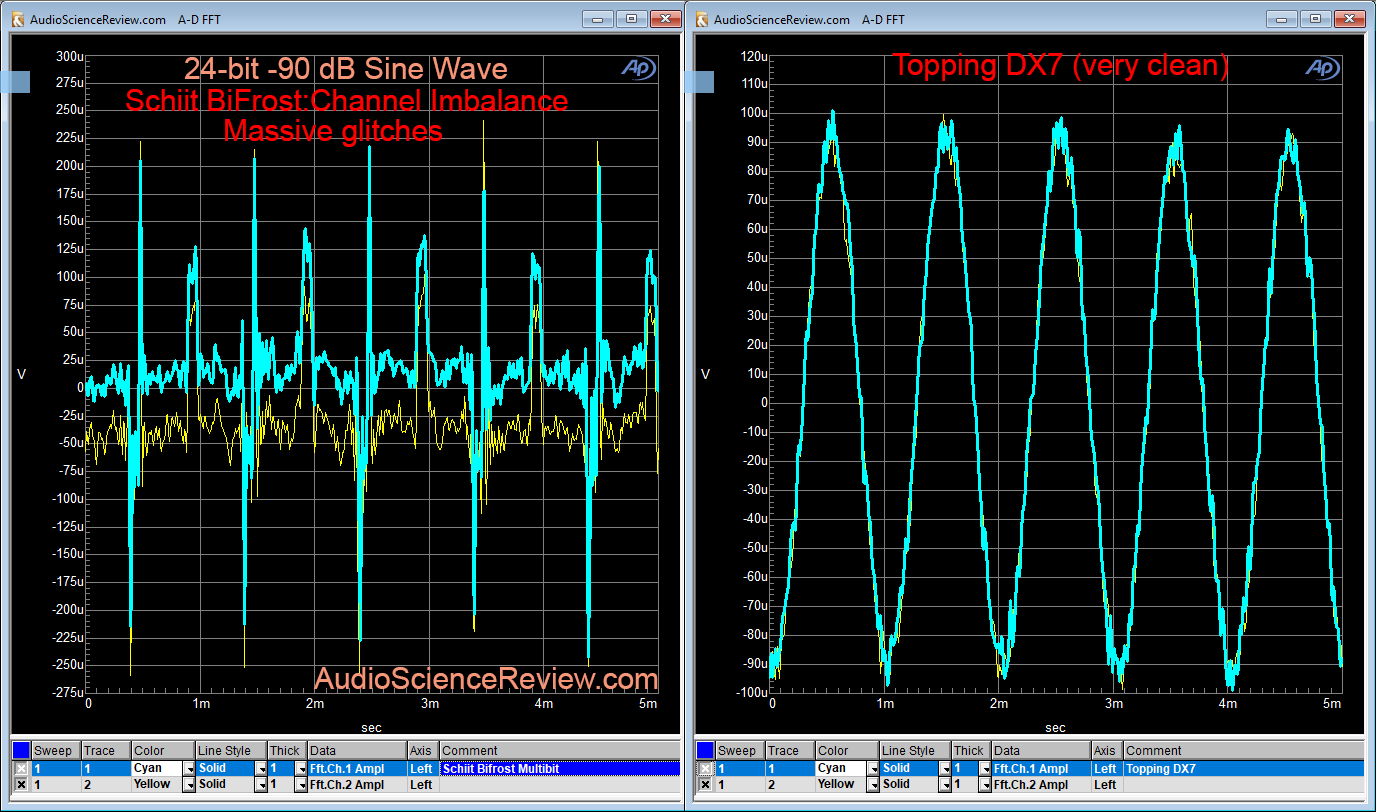

Distortions can be quite extreme as in this example on the left of the Schiit BiFrost Multibit:

There is just no ability to reproduce 16 bit audio samples correctly with the Schiit DAC on the left.

Harmonic Distortion

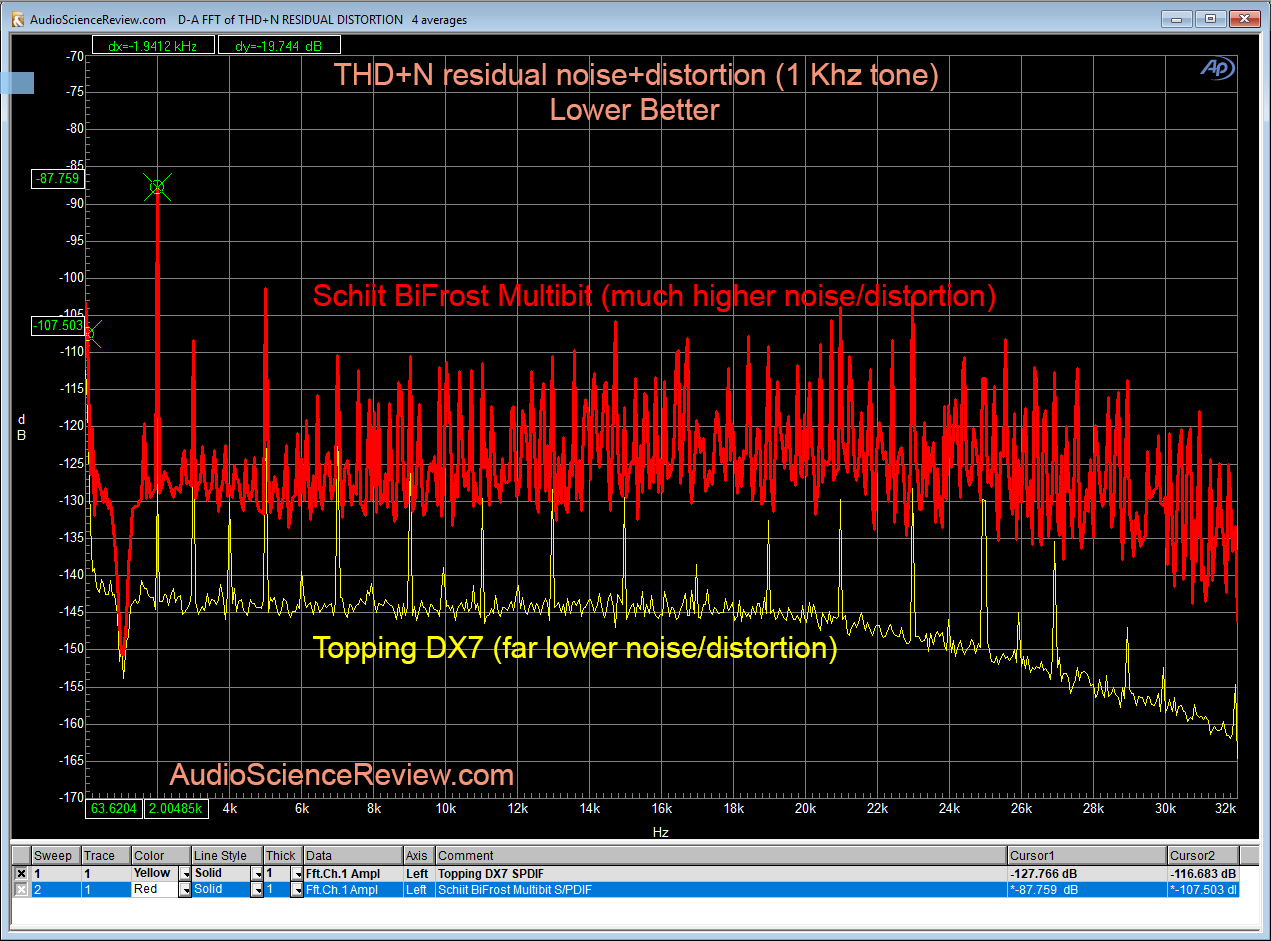

This is a classic test with a twist. We play a 1 kHz tone. We then take the output of the device and subtract that same 1 kHz tone. We then convert everything to frequency domain and plot its spectrum. What we see is both the noise floor and distortions represented as spikes:

Remember again the theory of masking. Earlier spikes are less audible that the later ones. In the above comparison we see tons more distortion products from Schiit BiFrost Multibit DAC relative to Topping DX7 which not only has a lower noise floor but its distortion peaks die down before the Schiit BiFrost Multibit start!

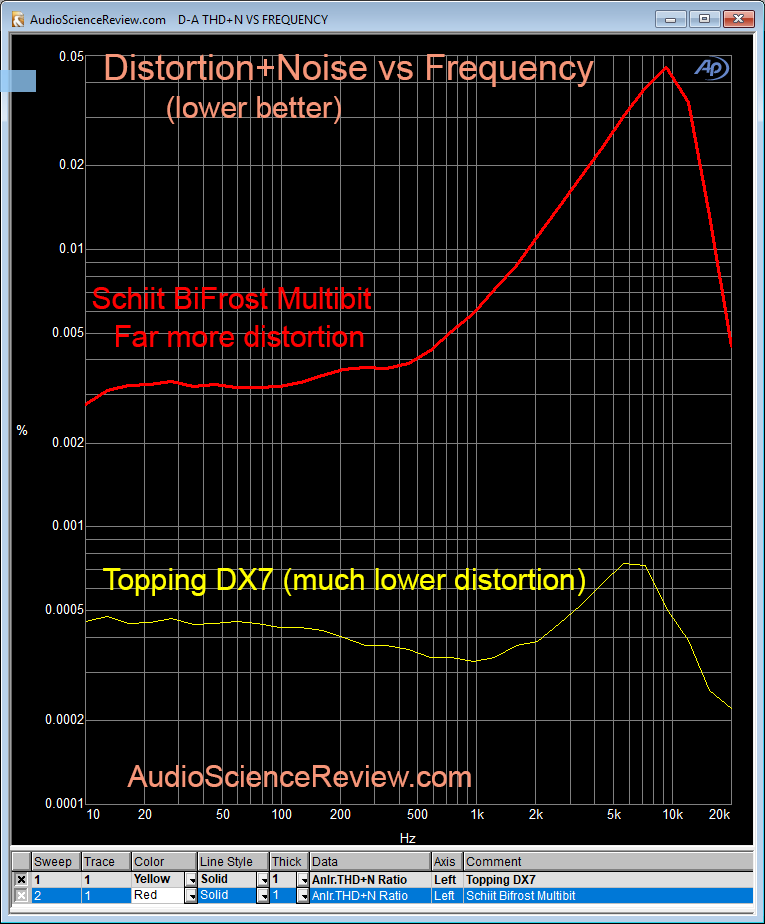

THD+N vs Frequency

This test shows the total harmonic distortion+noise at each frequency band:

Needless to say, the lower the better.

Perceptually THD+N is a rather poor metric since it considers all harmonic distortion products to have the same demerit. As I explained, from masking point of view, later spikes are more important than earlier ones. So don't get fixated on small differentials between devices being tested. Large differences like what is shown above though are significant and show the difference between good design/engineering and not so good ones.

Intermodulation Distortion

When an ideal linear system is fed two tones, it produces two tones. But when fed to a system with linearity errors, we get modulation frequencies above and below our two tones. This is called intermodulation distortion. There are many dual tone tests. For this, I have picked the SMPTE test which combines a low frequency (60 hz) with a high frequency (7 kHz) in a 4:1 ratio. Here is the explanation from Audio Precision:

The plotted output looks like this:

Again the lower the graph, the better.

As with THD+N this measurement is also psychoacoustically blind. So don't get fixated over small differences.

Equipment

The weapon of choice for me is the Audio Precision Sys-2522. Here is a picture of it in my rack (top box):

This is a very capable device able to work both in digital and analog domains. I can for example use the analog output in both balanced and unbalanced configuration to drive an amplifier, and measure its output again using either balanced or unbalanced inputs. In addition, it has digital output capable of generating both AES/EBU balanced and S/PDIF plus Toslink optical. All of these ports can be programmed to create jitter on demand to test robustness and fidelity of digital input on both consumer and professional equipment.

Retail price originally was around $25,000 which in today's prices is probably $40K. The box is rather old though and discontinued. Fear not. It is still exceptionally capable due to user interface and some of the processing being connected to a PC over USB. As such, it still operates like a workhorse. An ex-salesman for Audio Precision (AP) said in an online review that their biggest competition was ebay (i.e. used Audio Precisions)!

A bit of background on AP, Tektronix and HP used to own audio instrumentation (besides other domains). Their boxes were expensive but highly limited. A bunch of Tektronix engineers left and started Audio Precision where the UI functionality was in the PC as mentioned above. And the device was fully capable including such things as stereo measurements which the Tek/HP gear lacked. I heard about them when I was running engineering at Sony in early 1990s. Was almost going to buy an HP unit until I heard about AP. Could not believe how much better it was. So purchased the unit and found out no one in Sony Japan knew about it either.

The unit is no longer in calibration and I am in no mood to spent big bucks getting it calibrate. Such gear drifts very little and at any rate, you should be looking at measurements in relative mode and order magnitude. As an example if a distortion spike is at -130 graph, it could be a dB up or down. That doesn't matter to the type of analysis we are doing.

By the way, John Atkinson at Stereophile performs all of his measurements using almost as old a unit as mine (the AP 2700: see: https://www.stereophile.com/asweseeit/108awsi). I am pretty sure his is not calibrated recently either. So I am good company.

AP has upgraded their gear but all of their new units sans one underperform my analyzer! The only one that does better is the APX-555 series that retails for $28,000. One day I might upgrade to that but the difference in performance is not worth it right now. My analyzer is able to go deeper than threshold of hearing on many measurements.

Audio Precision and Rhode and Schwartz dominate the high-end of audio measurement field and demand high prices for them. You can buy cheaper units such as Prism Sound dSound which I have also used but you lose some performance in the front-end.

Theory of Operation

At high level, the Audio Precision is nothing more than an analog to digital converter. Input signals are digitized and then analyzed and reported as graphs. So in theory you could use a sound card to do the same thing. The big difference is that the AP is a known quantity so results can be replicated by others whereas sound card come in so many variations that comparing their results gets hard.

Another huge difference is the analog scalar front-end in AP. The controller in the analyzer is constantly monitoring input levels and scales them to the most ideal range for its ADC. This allows the internal ADC to work at its most linear and optimized level. In addition, the same logic allows measurements of high voltage inputs up to something like 150 volts! This is necessary for measurements of amplifier that can output such high voltages. If you connected an amp to a sound card input it would blow it up in an instant.

Signal Processing

Some of you may be wondering about a catch-22 issue: how can an older analog to digital converter keep up with the latest in digital to analog conversion? Wouldn't the noise from the old ADC dominate? The answer is no. Using signal processing we can achieve incredible amount of noise reduction. This occurs when we use the Fourier Transform ("FFT") to convert time domain signals to frequency. By using many audio samples, we are able to gain in the order of 32 db or so in noise reduction (called "FFT gain"). This allows us to dig deep to as low as -150 db looking for distortion products. This floor is well in excess of hearing dynamic range (around -116 dB).

Unfortunately this FFT gain is source of a lot of confusion. By increasing or decreasing the FFT gain, we can make the noise floor of a DAC better or worse on demand. Without compensation, graphs using different FFT sizes cannot be compared. I use 32K FFT which is a great balance between noise reduction and not having too much detail that is hard to interpret. I have seen measurements using 2 million point FFTs which produce extremely low measured noise floors that can mislead one quite well.

In addition averaging can be used to reduce variations in noise floor. Combined, these two techniques perform miracles in allowing is to measure analog output of equipment to incredible resolution.

The bottom line in cyan is the 32K FFT I use in all of my measurements unless noted otherwise. Notice how it has lowered the noise floor much more than the 256/1024 points. But importantly the noise floor is so low that we now see spikes that are 130 dB below our main tone at 12 kHz!!! The noise floor itself is at -140 dB which is way better than either the DAC or ADC can do (approaching 24 bits) let alone the combination of both. Such is the power of software and signal processing. Once in a while we get a free lunch.

Test Configuration

For above test, I ran the digital output from AP using a BNC to RCA adapter to a 3 foot coax cable which then connected to S/PDIF input of Pro-Ject. This is the same as you using a transport or USB to S/PDIF converter except that my analyzer is the source. Inside AP I can set the sampling rate and bit depth. The default for the J-test above is 24 bit, 48 kHz. I sometimes run 44.1 kHz. I am using 48 kHz because sometimes DACs are only optimized for 44.1 kHz and not 48 kHz (and multiples thereof).

The output of the DAC is unbalanced RCA which I connect back using a 6 foot or so, monster cable interconnects I have had for a couple of decades. It is a beefy cable with pretty tight RCA terminations.

Sometimes I test the balanced output of equipment. In that case I usually use a set of balanced cables I purchased from Audio Precision. They are kind of thin but very short so fine for testing.

For other tests like headphones I use either adapters from 3.5 mm/TRS to RCA or cables with those terminations on them. So nothing fancy here.

PC Testing

Toda many of us use external DACs with our computers using USB. For this reason I have converted some of my tests so that the source is generated by the computer but then captured and analyzed by the AP. For that, I use my normal everyday music player, Roon. In almost all cases I allow Windows 10 to detect the sound card and "gen up" the WASAPI interface which I use in exclusive, "bit-exact" mode. I usually capture the output of Roon format detection in my reviews. Here is the output for example for Pro-Ject Pre Box S2 Digital:

Roon has a nice indicator for when it is playing the file exactly or is converting it which is useful.

I used to use Foobar2000 which you may see in my older reviews to same effect.

Note that if Windows detects the device as is the case here, that is what I test. I only install drivers if I have to which thankfully these days is rare.

The computer I use for testing is my everyday laptop running Windows 10. It is an HP Z series "workstation." I am usually running other things on it while testing. No good DAC cares about that although some rare ones do (e.g. Schiit Modi 2). I have a Mac but have not done any work on it.

Tests

I will focus on DAC testing here which is most of what I do. Over time I will add to it for testing of other products.

j-Test for Jitter and Noise

My starter test is always the so called "J-Test." This is a special test which was developed by the late Julian Dunn which is the most recognized authority when it comes to standardizations and issues around serial digital audio transmission (i.e. AES/EBU and S/PDIF). He developed the J-Test signal as a way to increase amount of jitter which may be induced with the cable. And at the same time, it is a signal that is pure it its own.

J-Test is comprised of a square wave at 1/4 the frequency of the sampling rate. In the case of my default testing, sampling rate is 48 kHz so that square wave will become 12 kHz. Very oddly what comes out of the DAC is not a square wave but a sine wave! Why? Because to make a square wave you make a sine wave and then add to it infinite series of odd harmonics. The third harmonic will be the first addition at three times 12 kHz or 36 kHz. Because our sampling rate is 48 kHz, the DAC will filter out everything at half of that frequency or 24 kHz. Therefore none of the harmonics of that square wave get out. The only thing remaining is the first component which is a 12 kHz sine wave!!!

Why do we use a square wave as opposed to a 12 kHz sine wave? Well to create a sine wave we need to use fractional numbers. Digital audio samples on the other hand are all integers. We can convert those fractions to integers but we then must use some amount of noise as "dither" otherwise we create distortions. That raises the measured noise floor which is not good. Square wave on the other hand is just high or low numbers at fixed PCM values so we have no rounding/dither/noise to to add or worry about.

In addition to above, the J-Test signal varies with a fixed frequency to the tune of one bit. That one bit is designed to force all the bits to flip. Even though the level hardly changes, the effect on the cable and the receiver is significant. Normally this flipping bit will be visible in spectrum analysis when performing the test in 24 bits as I do. However, you never see it in my test since my FFT is not large enough to make it visible (you do see it in JA's stereophile tests). So from practical point of view, you can ignore everything I said in this paragraph.

The measurement you see posted above is the J-Test. We have our single peak in the middle representing the 12 kHz tone. Everything on the sides in an ideal DAC would be an infinitely low noise floor. Real DACs have higher noise floor and spikes here and there. If spikes are symmetrical around our main tone, they usually mean there is "jitter." Other spikes can exist by themselves indicating idle tones created due to interference or other problems in the DAC. In other words, the quieter the space around our 12 kHz peak, the better.

I usually show two devices on the same graph so that the contrast is easy to see. Here is an example from review of Schiit Modi 2:

As we see the iFi iDAC2 is much much cleaner than Schiit Modi 2. It has a flat, smooth noise floor whereas the Schiit Modi 2 has a bunch of distortion spikes (deterministic jitter) in addition to raised noise floor around our main 12 kHz tone (low frequency random jitter). The iFi iDAC2 is clearly superior.

Note that due to a psychoacoustics principle, jitter components hugging our main tone of 12 kHz are much less audible than the ones farther out from it. That distance is the jitter frequency. We can put this in the form of a graph as done by Julian Dunn:

Note: there is no jitter in the test signal itself. It is the nature of a higher frequency tone like 12 kHz to accentuate jitter because jitter correlates with how fast our signal is. Small clock differences don't matter to a slow low frequency wave like 60 Hz. But make it 12,000 Hz and small variations in clock to produce the next sample can become a much bigger deal.

It is said that J-Test is useless for non-S/PDIF interface. This is not so. Yes the bit toggling part was originally designed for AES/EBU and S/PDIF but the same toggling causes changes inside the DAC which can produce distortion/jitter/noise. And per above its 12 kHz tone is revealing just the same of jitter.

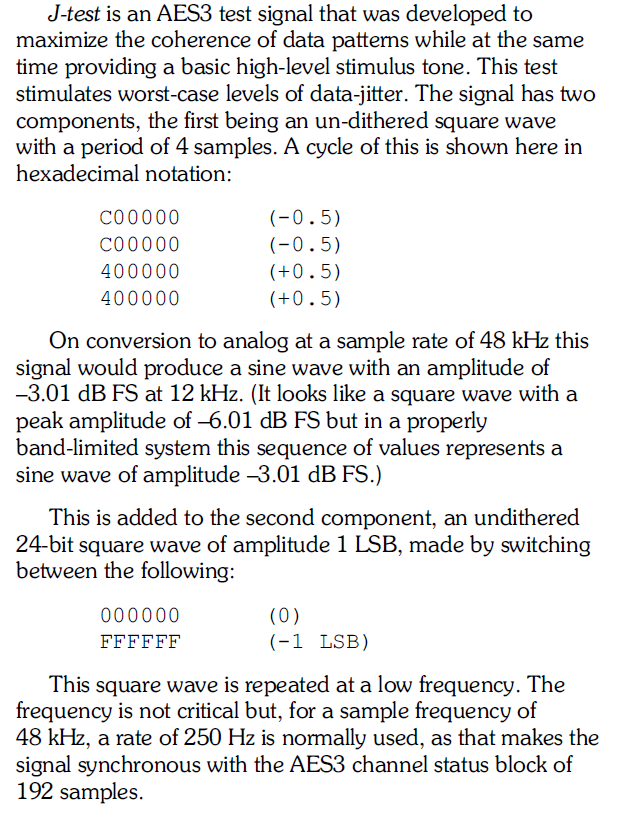

Here is Julian Dunn in his excellent write-up for Audio Precision on this topic:

While the above talks about AES/EBU balanced digital interface, the same is true of S/PDIF.

Linearity Test

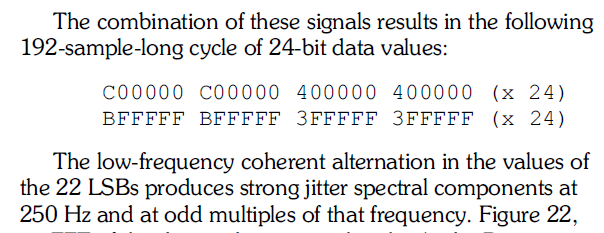

I run this test using the AP as the digital generator because it needs to be in control of changing the level. It produces a tone which it then makes smaller and smaller and compares the analog output to expected one from the digital samples:

I usually create a marker where the variation is around 0.1 dB of error. I then look up its amplitude (-112 dB above). I divide that by 6 and get what is called ENOB: effective number of bits. This gives you some idea of how accurate the DAC is in units of bits. Above we are getting about 18 bits.

Here is an example of a bad performing DAC, the Schiit BiFrost Multibit:

In an ideal situation we would have linearity going to 20+ bits. Reason for that is that in mid-frequencies absolute audible transparency would require about 120 db which is 20 bits * 6. As a lower threshold I like to see at least 16 bits of clean reproduction. No reason we can't play CDs/CD rips at 16 bits with any error after so many years since the introduction of that format.

Linearity Test Take 2

Another way to look at linearity is to see how a very small amplitude sine wave at just -90 dB can be reproduced using 24-bit samples and no dither. Put more simply we want to see if the rightmost bits in a 16-bit audio samples can be reproduced cleanly. If so, we should see a perfect sine wave. Here are two examples, first the Teac NT-503 and then Exasound E32:

The beauty of this measurement is that we can visually confirm accuracy. Any noise or incorrect conversion of digital to analog causes the waveform to deviate from ideal.

Distortions can be quite extreme as in this example on the left of the Schiit BiFrost Multibit:

There is just no ability to reproduce 16 bit audio samples correctly with the Schiit DAC on the left.

Harmonic Distortion

This is a classic test with a twist. We play a 1 kHz tone. We then take the output of the device and subtract that same 1 kHz tone. We then convert everything to frequency domain and plot its spectrum. What we see is both the noise floor and distortions represented as spikes:

Remember again the theory of masking. Earlier spikes are less audible that the later ones. In the above comparison we see tons more distortion products from Schiit BiFrost Multibit DAC relative to Topping DX7 which not only has a lower noise floor but its distortion peaks die down before the Schiit BiFrost Multibit start!

THD+N vs Frequency

This test shows the total harmonic distortion+noise at each frequency band:

Needless to say, the lower the better.

Perceptually THD+N is a rather poor metric since it considers all harmonic distortion products to have the same demerit. As I explained, from masking point of view, later spikes are more important than earlier ones. So don't get fixated on small differentials between devices being tested. Large differences like what is shown above though are significant and show the difference between good design/engineering and not so good ones.

Intermodulation Distortion

When an ideal linear system is fed two tones, it produces two tones. But when fed to a system with linearity errors, we get modulation frequencies above and below our two tones. This is called intermodulation distortion. There are many dual tone tests. For this, I have picked the SMPTE test which combines a low frequency (60 hz) with a high frequency (7 kHz) in a 4:1 ratio. Here is the explanation from Audio Precision:

The stimulus is a strong low-frequency interfering signal (f1) combined with a weaker high frequency signal of interest (f2). f1 is usually 60 Hz and f2 is usually 7 kHz, at a ratio of f1_f2=4:1. The stimulus signal is the sum of the two sine waves. In a distorting DUT, this stimulus results in an AM (amplitude modulated) waveform, with f2 as the “carrier” and f1 as the modulation.

In analysis, f1 is removed, and the residual is bandpass filtered and then demodulated to reveal the AM modulation products. The rms level of the modulation products is measured and expressed as a ratio to the rms level of f2. The SMPTE IMD measurement includes noise within the passband, and is insensitive to FM (frequency modulation) distortion.

In analysis, f1 is removed, and the residual is bandpass filtered and then demodulated to reveal the AM modulation products. The rms level of the modulation products is measured and expressed as a ratio to the rms level of f2. The SMPTE IMD measurement includes noise within the passband, and is insensitive to FM (frequency modulation) distortion.

The plotted output looks like this:

Again the lower the graph, the better.

As with THD+N this measurement is also psychoacoustically blind. So don't get fixated over small differences.

Last edited: