Punter

Active Member

- Joined

- Jul 19, 2022

- Messages

- 233

- Likes

- 1,142

The year is 1877 and Thomas Edison presents his “Phonograph” to the world. It wasn’t the only device able to reproduce recorded sound but it was the most reliable. The medium in this early machine was the “Brown Wax” cylinder, which was not actually composed of wax but made of a metal soap composed of stearic acid and aluminium powder. This metallic soap was brittle but it had a waxy surface that assisted the playing process and meant that the cylinder could tolerate many playing cycles. One significant downside with this technology was the lack of any mechanism to duplicate cylinders. For a band or artist to have 100 cylinders to sell, they would have to set up an array of phonographs to record their performance and then reload all of the recorders and play it all over again to create multiple copies.

Later, mechanical duplicators were created with two styli. One stylus ran in the groove of the “master” and the other cut a duplicate groove in a blank cylinder via a pantograph mechanism. The problem of mass duplication was overcome with the introduction of the “Black Wax” cylinder, a harder composite which could be moulded from a gold master. The process involved creating a metallic gold mould from a wax master; a wax blank could then be put inside the mould and subjected to a precisely calibrated level of heat. As the blank expanded, the grooves would be pressed into the blank, and after cooling, the newly created cylinder would shrink and could be removed from the mould.

Cylinders evolved through a few permutations subsequently. There was the “Amberol” cylinder that upped the pitch of the groove from 100 to 200 grooves per inch, thus doubling the playing time of the recording from two to four minutes. Then, finally, the “Blue Amberol” cylinders. Edison didn’t have the market to themselves however, there were competing cylinders from Columbia and Pathé to name a couple. The final permutation of the cylinder record was the celluloid variety which was much more durable than the wax cylinder but they haven’t aged well, often shrinking and warping. Wax cylinders have proved much more stable over time even if they are extremely brittle.

Cylinders peaked in popularity around 1905. After this, discs and disc players, most notably the Victrolas, began to dominate the market. Columbia Records, an Edison competitor, had stopped marketing cylinders in 1912. The Edison Company had been fully devoted to cylinder phonographs, but, concerned with discs' rising popularity, Edison associates began developing their own disc player and discs in secret.

Despite Edisons best efforts, his style of disc failed to become the dominant style. Edisons groove was vertical-plane, where the needle bobbed up and down but the competition, Columbia, Victor and HMV all adopted the lateral-plane groove where the needle moved side to side. Disc speeds varied from 78rpm to 90rpm(for Edison) but eventually, the Shellac 78 with a lateral groove became the dominant format. In early phonographs, the stylus was made of steel and needed to be changed frequently. As phonographs evolved, the use of a jewel stylus became a point of difference and was mass produced first by His Masters Voice.

During WWII, Shellac started to become unavailable due to it’s use in munitions and a new substance, Polyvinyl Chloride started to be employed for phonograph discs. Interestingly, such was the demand for shellac that there were “record drives” where people donated their shellac records to the war effort.

The next development in the history of the vinyl disc was the advent of the 33+1⁄3 rpm disc in the form of “Transcription” discs that were 16 inches in diameter with a playing time of around 15 minutes. These discs were primarily used in the broadcast industry and were never intended for domestic use. As broadcast was a mono medium, so were 16” transcription discs. Depending on the era, some transcription discs were inside start, where the stylus was placed in the area of the record we consider the runout and the disc would proceed to play to the outside edge.

More pertinent to the domestic audience, the first 12 inch, “Microgroove” long playing (LP) records were launched by Columbia in 1948. The groove was 0.003 inches and this enabled each side to play for around 22 minutes. The launch LP was Columbia ML4001, the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E Minor with soloist Nathan Milstein, and Bruno Walter conducting the Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra of New York.

Despite the convenience of having 22 minutes between disc flipping, the LP wasn’t a runaway success with sales figures in 1952 showing 78’s having approximately 50% of sales with the remainder split between LP’s and 45’s (introduced by RCA Victor in 1949), LP’s having only 17%. This can probably be explained by the inertia of existing equipment in the market. By 1958, the picture had changed significantly with 78’s dropping to a mere 2%.

The final element for the vinyl gramophone record, stereo, had to wait until 1957 to be realised. Despite several major record companies having the Westrex mastering lathes that could cut the stereo groove, it was left to a much smaller company to release the first stereophonic vinyl disc. Audio Fidelity Records, a record company based in New York City, created the first mass-produced American stereophonic long-playing record in November 1957 (although this was not available to the general public until March of the following year). The disc contained a performance by the Dukes of Dixieland on Side 1. Side 2 was railroad sound effects which was intended to really show off the capabilities of the stereophonic format. The disc was mastered on a Westrex lathe and approximately 500 discs were made in the first pressing. Even though this was the first incarnation of the stereo LP, stereo recordings had been available on tape since 1950. In fact, tape was seen as a serious competitor to the disc and the two formats continued to battle it out right up until the advent of the Compact Disc.

The method of mastering a stereo disc had to have one critical feature in the early days, it had to be compatible with mono playback equipment. The angle taken by Westrex eventually became the standard. In the Westrex system, uses two modulation angles, equal and opposite 45 degrees from vertical (and so perpendicular to each other.) It can also be thought of as using traditional horizontal modulation for the sum of left and right channels (mono), making it essentially compatible with mono playback equipment, and vertical-plane modulation for the difference of the two channels. So the record groove actually represents an audio matrix rather than two discreet channels.

So we have stereo records but what about the equipment to play it on? In the 50’s the gramophone was often in the form of a (quite expensive) piece of furniture commonly referred to as a “console”. These units usually combined an amplifier, a radio receiver and a turntable. As with the advent of the 33 1/3 rpm disc, there was some inertia in the market with respect to the adoption of stereo-capable equipment. Subsequently, companies like Magnavox began producing stereo upgrade kits for their consoles. One notable example was the add-on kit for the Magnavox Continental

Another essential component was a stereo pickup cartridge with one of the original units being the Shure M3D which was developed in concert with the development of the stereo LP by Columbia, hence why both products were launched at the same time. Other notable manufacturers were Grado and Fairchild. The Shure was a moving magnet design where the Grado and Fairchild were moving coil. All of these manufacturers were producing mono pickups prior to the advent of stereo recordings so there wasn’t anything revolutionary about the designs, all they had to do was convert the stereo groove matrix from vibration to electricity. With all of the pieces of the puzzle now in place, it could be said that the concept of “High Fidelity “ was now realised even though the development of the silicon transistor would take the concept to its current state with so many manufacturers and products.

Up until the advent of the Compact Disc, Vinyl records were the gold standard for High Fidelity audio reproduction. Tape may have been a threat in the mono days but as a domestic technology, it never seriously challenged vinyl. Even the advent of the Compact Cassette didn’t steal vinyls crown as its limitations were well known. Cassettes were convenient but they didn’t win on sound quality despite the addition of noise reduction systems like Dolby. This market domination is testament to the brilliant minds who devised the technology around creating vinyl records and their ability to overcome the many limitations of the format.

So how did you make a HiFi Stereo Record in the tape era?

The process of creating a record begins with the mastering process on quarter inch tape. This is the ultimate destination of the performance that has been recorded on multi track tape in the studio. The master usually consists of two separate tapes for the A and B side of the disc. Great care must be taken to prepare the master recording to fit the requirements of the disc mastering process. These requirements are part and parcel of keeping the audio in a fit state to pass onto the lathe that will cut the disc master. The process has many limitations where it comes to amplitude and frequency, there are thresholds that can’t be exceeded and you don’t want to take the risk that you will run a mastering session on the lathe where you turn out an unplayable cut.

It is necessary to make the following adjustments to the master recording prior to having it transcribed to disc.

Low frequencies up to 150hz should be kept mono, this will make for a more focussed stereo image and also enable the lathe to create a trackable groove. Vinyl records have their biggest limitations at the lower and upper end of the audible frequency spectrum.

Attenuate sibilance-range frequencies. Sibilance-range frequencies typically occupy 3kHz to 10kHz, but will very much vary depending on the content of the song. Attenuating these frequencies is important to avoid distortion on a record.

Use compression to control any excessive dynamics. During a traditional mastering session, compression is used to control dynamics. This is done to balance the dynamics, avoid distortion, and allow for pushing the signal into a louder territory. When mastering for vinyl, controlling dynamics takes on a different and wholly unique purpose. If a metal master used for cutting a lacquer is too dynamic, then the greater amplitude will cause a significant cut into the lacquer. The significant cut can cause consumer-grade needles to jump out of place, and cause what is often referred to as a skipping record. With that said, greater amounts of compression or dynamic control may be needed to adequately prepare a master for the vinyl cutting process.

Gently introduce low-level automatic gain control (AGC). This step may be less obvious but is important nonetheless. Because we’re avoiding limiting or significant limiting when mastering for vinyl, this means that the quieter aspects of a recording will not be amplified to roughly the same level of the formerly loudest aspects of the master. As a result, the quieter aspects of the recording will remain somewhat unperceivable and maybe lost on the listener. Fortunately, low-level AGC can be used to augment these aspects and make them more perceivable to the listener.

Sequence the tracks to avoid excessive sibilance toward the record’s centre. Unlike a digital format, the vinyl record has distinct physical limitations that affect the sound source imparted onto it. This is true for the dynamic range, the frequency spectrum, the stereo image, the amount of distortion introduced, and many other smaller factors. One of the most notable and perhaps more interesting effects is how the shape of the vinyl record, eventually causes higher frequencies to be attenuated, the closer the needle gets toward the centre. In short, the record spins at a constant rate. This means the needle is traveling at the same speed; however, the distance the needle is traveling is constantly changing. This is due to the groove in which a needle is placed becoming smaller and smaller the closer the gets to the centre of the record. As a result, the velocity of the needle decreases, and the higher frequencies are no longer able to be replicated by the needle.

The shortcomings of the vinyl disc mean that several audio factors need to be addressed to ensure an error-free mastering-to-disc process. A previously mentioned, high frequencies and low frequencies both have to be controlled. The most universal limitation is amplitude. Big transients and amplitudes can cause several problems on the disc master. A transient like a cannon shot on the 1612 overture could cause a transient that a playback stylus can’t track. It could also create a breakthrough where the transient breaks through to the previously cut section of groove opposite. Finally, it could create a “pre-echo” where the transient distorts the previously cut section of the groove opposite. This is primarily an effect with low frequencies and why this end of the spectrum comes in for some serious attention by the mastering engineer. Next is the turn of high frequencies, excessive amplitude at the high end of the spectrum can once again cause playback tracking issues but at the lathe, if a Direct Metal Master (DMM) is being cut, these frequencies can damage the delicate heater wires used in the cutting head. In addition to this, the cutting stylus may hit its threshold and not be able to accurately cut those frequencies.

Finally, the RIAA equalisation curve is applied to the audio via the lathe electronics. There’s plenty of information about this so I won’t go into a detailed explanation here.

Over the years, various techniques have been developed to improve the quality of vinyl records one of which is Vari-pitch (variable pitch) an engineer can pack grooves tightly together during the quiet passages of a song then automatically create more space when the signal gets louder. The effect of this is to either yield more playing time or can be used to allow bigger transients without needing to uniformly space the pitch out to accommodate them.

Another technique is “Half Speed Mastering”. In the case of half-speed mastering, the whole process is slowed down to, you guessed it, half of the original speed. In other words, a typical 33 1/3 rpm record is cut at 16 2/3rpm. The source material is also slowed down (reducing the pitch in the process) meaning the final record will still sound normal when played back. The advantage with this technique is to drastically reduce the stress on the cutting head and stylus. At half speed, high frequencies will be cut far more accurately and big transients can be accommodated more easily.

Interestingly, since the mid-1970s, vinyl mastering houses began using digital delay lines instead of analogue delays on the signal going to the lathe. So even in the increasingly unlikely event that 100% of the recording, mixing and mastering was done entirely using analogue gear and media, the end of the vinyl mastering process may well have involved a conversion to digital and back to achieve half-speed mastering.

The Record Mastering Lathe

To the lathe itself. Simplistically, it can be seen as a thread cutting machine except the thread is a flat groove rather than a cylindrical one. Much has been written about these machines but the technology seems to have peaked with the Neumann VMS 80 paired with an SX-74 cutting head which was capable of DMM. Unsurprisingly, the manufacturing and development of lathes pretty much ceased after the arrival of the CD. Subsequently, top quality lathes like the Neumann command substantial prices when they (rarely) come up for sale. From the picture it’s possible to understand the way the cutting head moves in a linear fashion across the mastering medium. There is also a conventional tonearm on the machine and a microscope. The tone arm can be used to test a master if it’s DMM but lacquer masters have to be handled with extreme care and cannot be played. The final processes to produce a pressing master involves the metal plating of the lacquer master or a lacquer that has been lifted from a DMM master.

Finally, there is a vinyl LP record that can be shipped out and purchased by an eager punter but what are they getting? Are they getting a faithful recording of an artist or group? I would say no but it’s the best you can get if your medium is a vinyl LP record. The amount of processing and manipulation of the recorded sound to accommodate the limitations of vinyl are significant and will have limited a range of characteristics in the music being reproduced by the users equipment. High and low frequencies have had to be rolled off or limited so that they don’t ruin the master on the lathe. The RIAA curve has been applied at the lathe and then reversed in the phono preamp of the users equipment. Add this to the almost unlimited amount of manipulation that can be applied at the multi-track recording stage and it can be observed that there is an accumulation of processing in the end-to-end process. Vinyl has limited dynamic range, particularly when compared to digital recording methods. The practical dynamic range is normally somewhere between 20 and 40dB but some claim that it can be as high as 80dB but this is likely only under very specific circumstances as 80dB would take up a lot of room on the disc surface. By contrast, the dynamic range of a CD is 150dB without any special conditions needed. Opinions vary as to the actual frequency range of a vinyl LP. There are reports that they are capable of reproducing supersonic frequencies maybe as high as 100KHz. However, the high frequencies are a moot point as the RIAA preamp will only pass frequencies from 20Hz to 20KHz. The low end is less spectacular with a realistic threshold of around 24Hz. Finally, the last factor affecting the perceived stereo image is channel separation which generally gets worse at higher frequencies. The actual value is seldom more than around 20dB of separation and this value degrades with mistracking and incorrect stylus height/angle. Mistracking is inevitable in a pivoted arm as the master is cut with a linear mechanism. The closer the stylus gets to the centre of the LP, the bigger the tracking error. A linear tonearm will overcome this issue but as can be observed, there aren’t many of them due to the complicated nature of arranging a low friction linear mechanism which will allow the kind of mechanical properties needed for accurate tracking.

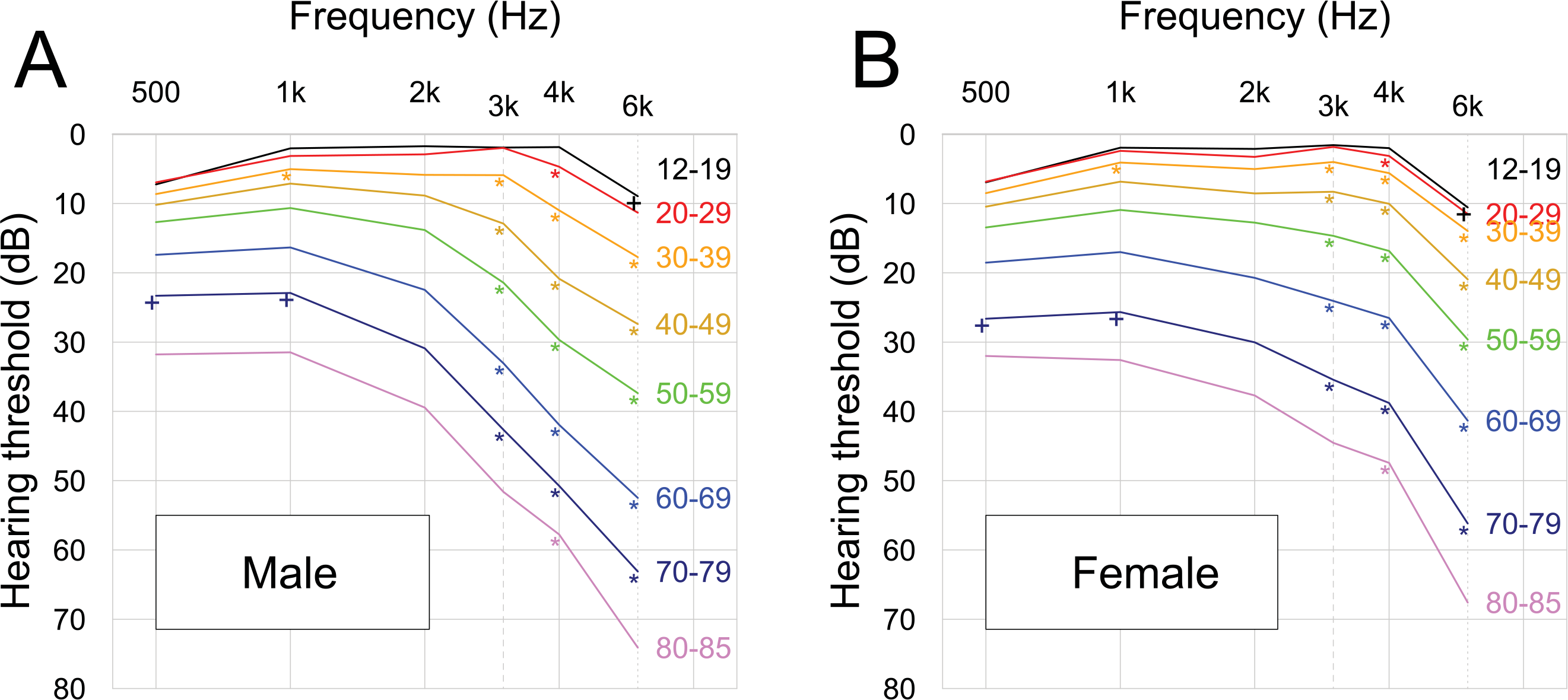

In addition to all of these defects, the actual frequency response of the listeners’ ears has a bearing on how the reproduced sound is perceived. If the listener is male and over 40 years old, it’s likely that the individuals’ ability to hear any frequency above 10 KHz is severely compromised.

At the end of the day, a vinyl record is a severely compromised form of recorded audio. The limitations on channel separation and dynamic range both conspire to reduce the psychological impression of a stereo image.

So how far should the end user go in the form of equipment and expense to listen to this medium? From what we have learned, the answer could be “go far enough so that the equipment doesn’t make the sound any worse” In which case it would be appropriate to look at factors that could make the sound worse.

Rumble.

Vinyl has inherent noise problems which the RIAA circuit attempts to mask but the playback device, in the form of a turntable, could actually add a signature of its own in the form of mechanical noise. Rumble is generated by the drive mechanism for the turntable and indicates low quality bearings in the platter spindle and possibly the motor. Some low cost turntables use a wheel with a rubber tire running on the rim of the platter for drive which will undoubtedly generate unwanted noise and vibrations. Excellent direct drive mechanisms have been designed over the years with one of the best being the Technics SP10 (SL-150 in HiFi form) which has excellent speed stability and extremely low rumble at -70dB, well below any that would be generated by the disc itself. The current audiophile seems to favour belt drive as almost all “High End” turntables are driven this way. Belt drive is inferior to a well-designed direct drive but it’s simple and potentially adds some mechanical isolation between the drive motor and the platter.

Mistracking.

As previously described, using a pivot style tonearm will inevitably cause tracking error towards the centre of the record. The only remedy to this is an effective linear tracking tonearm.

Wow and Flutter.

Once again this is down to the drive mechanism on the platter. To counter this the platter needs to have an adequate amount of weight to achieve a stable speed by dint of the flywheel effect, where the inertia of the rotating platter stores some energy and will tend to flatten out any cogging from the drive mechanism. A direct drive platter is more like the rotating element of an AC motor and can achieve very stable speed by the application of a multi-phase AC drive circuit.

Isolation.

The turntable should have some way to resist or damp out external vibration especially low frequency energy that can be generated by the speakers themselves. In extreme situations, a positive feedback loop can get established that will adversely affect the playback.

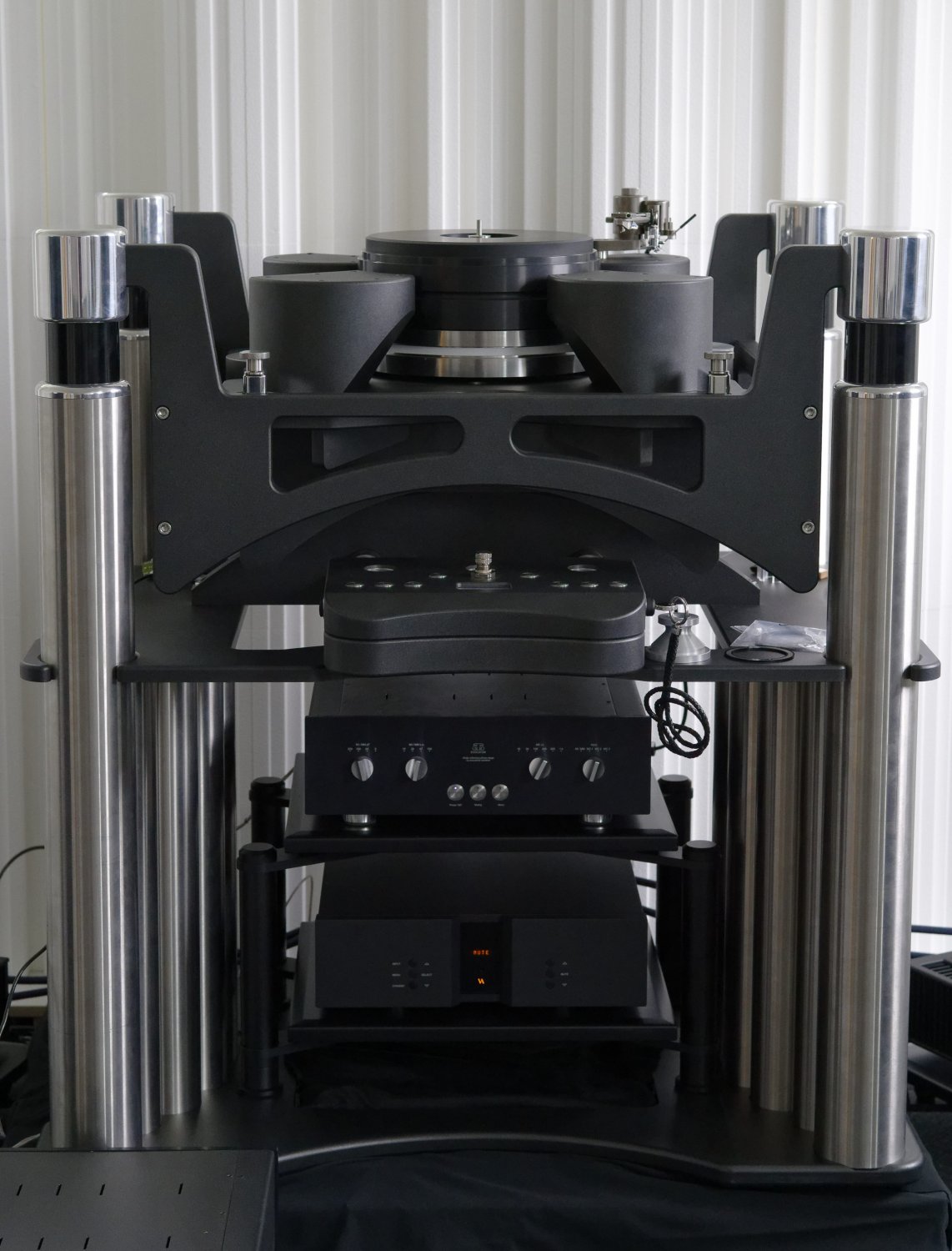

Based on all of these factors, what then constitutes a device which will spin a vinyl disc at 33.333rpm and not add any unwanted elements? There are probably quite a lot of turntables that would cover the brief. One that springs to mind is the Rega Planar. Despite its modest price, it’s built with high quality components and will allow a user to play a vinyl disc as accurately as is possible with a pivoting tonearm.

Little more can be gained in the form of reproduction by drastically increasing the weight or mechanical complexity of the turntable especially when that specification would actually exceed that of the disc lathe that created the master.

Don’t forget, the reproduction equipment cant put back what is missing from the disc mastering process. Speaking of which, due to the the amount of missing and compromised information on an LP, it can’t really be considered “HiFi” in the current era. Compared to the excellent capabilities of digital recording, especially in the area of dynamic range, noise, wow & flutter and accuracy, a vinyl LP and it’s playing method is thoroughly primitive.

Later, mechanical duplicators were created with two styli. One stylus ran in the groove of the “master” and the other cut a duplicate groove in a blank cylinder via a pantograph mechanism. The problem of mass duplication was overcome with the introduction of the “Black Wax” cylinder, a harder composite which could be moulded from a gold master. The process involved creating a metallic gold mould from a wax master; a wax blank could then be put inside the mould and subjected to a precisely calibrated level of heat. As the blank expanded, the grooves would be pressed into the blank, and after cooling, the newly created cylinder would shrink and could be removed from the mould.

Cylinders evolved through a few permutations subsequently. There was the “Amberol” cylinder that upped the pitch of the groove from 100 to 200 grooves per inch, thus doubling the playing time of the recording from two to four minutes. Then, finally, the “Blue Amberol” cylinders. Edison didn’t have the market to themselves however, there were competing cylinders from Columbia and Pathé to name a couple. The final permutation of the cylinder record was the celluloid variety which was much more durable than the wax cylinder but they haven’t aged well, often shrinking and warping. Wax cylinders have proved much more stable over time even if they are extremely brittle.

Cylinders peaked in popularity around 1905. After this, discs and disc players, most notably the Victrolas, began to dominate the market. Columbia Records, an Edison competitor, had stopped marketing cylinders in 1912. The Edison Company had been fully devoted to cylinder phonographs, but, concerned with discs' rising popularity, Edison associates began developing their own disc player and discs in secret.

Despite Edisons best efforts, his style of disc failed to become the dominant style. Edisons groove was vertical-plane, where the needle bobbed up and down but the competition, Columbia, Victor and HMV all adopted the lateral-plane groove where the needle moved side to side. Disc speeds varied from 78rpm to 90rpm(for Edison) but eventually, the Shellac 78 with a lateral groove became the dominant format. In early phonographs, the stylus was made of steel and needed to be changed frequently. As phonographs evolved, the use of a jewel stylus became a point of difference and was mass produced first by His Masters Voice.

During WWII, Shellac started to become unavailable due to it’s use in munitions and a new substance, Polyvinyl Chloride started to be employed for phonograph discs. Interestingly, such was the demand for shellac that there were “record drives” where people donated their shellac records to the war effort.

The next development in the history of the vinyl disc was the advent of the 33+1⁄3 rpm disc in the form of “Transcription” discs that were 16 inches in diameter with a playing time of around 15 minutes. These discs were primarily used in the broadcast industry and were never intended for domestic use. As broadcast was a mono medium, so were 16” transcription discs. Depending on the era, some transcription discs were inside start, where the stylus was placed in the area of the record we consider the runout and the disc would proceed to play to the outside edge.

More pertinent to the domestic audience, the first 12 inch, “Microgroove” long playing (LP) records were launched by Columbia in 1948. The groove was 0.003 inches and this enabled each side to play for around 22 minutes. The launch LP was Columbia ML4001, the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E Minor with soloist Nathan Milstein, and Bruno Walter conducting the Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra of New York.

Despite the convenience of having 22 minutes between disc flipping, the LP wasn’t a runaway success with sales figures in 1952 showing 78’s having approximately 50% of sales with the remainder split between LP’s and 45’s (introduced by RCA Victor in 1949), LP’s having only 17%. This can probably be explained by the inertia of existing equipment in the market. By 1958, the picture had changed significantly with 78’s dropping to a mere 2%.

The final element for the vinyl gramophone record, stereo, had to wait until 1957 to be realised. Despite several major record companies having the Westrex mastering lathes that could cut the stereo groove, it was left to a much smaller company to release the first stereophonic vinyl disc. Audio Fidelity Records, a record company based in New York City, created the first mass-produced American stereophonic long-playing record in November 1957 (although this was not available to the general public until March of the following year). The disc contained a performance by the Dukes of Dixieland on Side 1. Side 2 was railroad sound effects which was intended to really show off the capabilities of the stereophonic format. The disc was mastered on a Westrex lathe and approximately 500 discs were made in the first pressing. Even though this was the first incarnation of the stereo LP, stereo recordings had been available on tape since 1950. In fact, tape was seen as a serious competitor to the disc and the two formats continued to battle it out right up until the advent of the Compact Disc.

The method of mastering a stereo disc had to have one critical feature in the early days, it had to be compatible with mono playback equipment. The angle taken by Westrex eventually became the standard. In the Westrex system, uses two modulation angles, equal and opposite 45 degrees from vertical (and so perpendicular to each other.) It can also be thought of as using traditional horizontal modulation for the sum of left and right channels (mono), making it essentially compatible with mono playback equipment, and vertical-plane modulation for the difference of the two channels. So the record groove actually represents an audio matrix rather than two discreet channels.

So we have stereo records but what about the equipment to play it on? In the 50’s the gramophone was often in the form of a (quite expensive) piece of furniture commonly referred to as a “console”. These units usually combined an amplifier, a radio receiver and a turntable. As with the advent of the 33 1/3 rpm disc, there was some inertia in the market with respect to the adoption of stereo-capable equipment. Subsequently, companies like Magnavox began producing stereo upgrade kits for their consoles. One notable example was the add-on kit for the Magnavox Continental

Another essential component was a stereo pickup cartridge with one of the original units being the Shure M3D which was developed in concert with the development of the stereo LP by Columbia, hence why both products were launched at the same time. Other notable manufacturers were Grado and Fairchild. The Shure was a moving magnet design where the Grado and Fairchild were moving coil. All of these manufacturers were producing mono pickups prior to the advent of stereo recordings so there wasn’t anything revolutionary about the designs, all they had to do was convert the stereo groove matrix from vibration to electricity. With all of the pieces of the puzzle now in place, it could be said that the concept of “High Fidelity “ was now realised even though the development of the silicon transistor would take the concept to its current state with so many manufacturers and products.

Up until the advent of the Compact Disc, Vinyl records were the gold standard for High Fidelity audio reproduction. Tape may have been a threat in the mono days but as a domestic technology, it never seriously challenged vinyl. Even the advent of the Compact Cassette didn’t steal vinyls crown as its limitations were well known. Cassettes were convenient but they didn’t win on sound quality despite the addition of noise reduction systems like Dolby. This market domination is testament to the brilliant minds who devised the technology around creating vinyl records and their ability to overcome the many limitations of the format.

So how did you make a HiFi Stereo Record in the tape era?

The process of creating a record begins with the mastering process on quarter inch tape. This is the ultimate destination of the performance that has been recorded on multi track tape in the studio. The master usually consists of two separate tapes for the A and B side of the disc. Great care must be taken to prepare the master recording to fit the requirements of the disc mastering process. These requirements are part and parcel of keeping the audio in a fit state to pass onto the lathe that will cut the disc master. The process has many limitations where it comes to amplitude and frequency, there are thresholds that can’t be exceeded and you don’t want to take the risk that you will run a mastering session on the lathe where you turn out an unplayable cut.

It is necessary to make the following adjustments to the master recording prior to having it transcribed to disc.

Low frequencies up to 150hz should be kept mono, this will make for a more focussed stereo image and also enable the lathe to create a trackable groove. Vinyl records have their biggest limitations at the lower and upper end of the audible frequency spectrum.

Attenuate sibilance-range frequencies. Sibilance-range frequencies typically occupy 3kHz to 10kHz, but will very much vary depending on the content of the song. Attenuating these frequencies is important to avoid distortion on a record.

Use compression to control any excessive dynamics. During a traditional mastering session, compression is used to control dynamics. This is done to balance the dynamics, avoid distortion, and allow for pushing the signal into a louder territory. When mastering for vinyl, controlling dynamics takes on a different and wholly unique purpose. If a metal master used for cutting a lacquer is too dynamic, then the greater amplitude will cause a significant cut into the lacquer. The significant cut can cause consumer-grade needles to jump out of place, and cause what is often referred to as a skipping record. With that said, greater amounts of compression or dynamic control may be needed to adequately prepare a master for the vinyl cutting process.

Gently introduce low-level automatic gain control (AGC). This step may be less obvious but is important nonetheless. Because we’re avoiding limiting or significant limiting when mastering for vinyl, this means that the quieter aspects of a recording will not be amplified to roughly the same level of the formerly loudest aspects of the master. As a result, the quieter aspects of the recording will remain somewhat unperceivable and maybe lost on the listener. Fortunately, low-level AGC can be used to augment these aspects and make them more perceivable to the listener.

Sequence the tracks to avoid excessive sibilance toward the record’s centre. Unlike a digital format, the vinyl record has distinct physical limitations that affect the sound source imparted onto it. This is true for the dynamic range, the frequency spectrum, the stereo image, the amount of distortion introduced, and many other smaller factors. One of the most notable and perhaps more interesting effects is how the shape of the vinyl record, eventually causes higher frequencies to be attenuated, the closer the needle gets toward the centre. In short, the record spins at a constant rate. This means the needle is traveling at the same speed; however, the distance the needle is traveling is constantly changing. This is due to the groove in which a needle is placed becoming smaller and smaller the closer the gets to the centre of the record. As a result, the velocity of the needle decreases, and the higher frequencies are no longer able to be replicated by the needle.

The shortcomings of the vinyl disc mean that several audio factors need to be addressed to ensure an error-free mastering-to-disc process. A previously mentioned, high frequencies and low frequencies both have to be controlled. The most universal limitation is amplitude. Big transients and amplitudes can cause several problems on the disc master. A transient like a cannon shot on the 1612 overture could cause a transient that a playback stylus can’t track. It could also create a breakthrough where the transient breaks through to the previously cut section of groove opposite. Finally, it could create a “pre-echo” where the transient distorts the previously cut section of the groove opposite. This is primarily an effect with low frequencies and why this end of the spectrum comes in for some serious attention by the mastering engineer. Next is the turn of high frequencies, excessive amplitude at the high end of the spectrum can once again cause playback tracking issues but at the lathe, if a Direct Metal Master (DMM) is being cut, these frequencies can damage the delicate heater wires used in the cutting head. In addition to this, the cutting stylus may hit its threshold and not be able to accurately cut those frequencies.

Finally, the RIAA equalisation curve is applied to the audio via the lathe electronics. There’s plenty of information about this so I won’t go into a detailed explanation here.

Over the years, various techniques have been developed to improve the quality of vinyl records one of which is Vari-pitch (variable pitch) an engineer can pack grooves tightly together during the quiet passages of a song then automatically create more space when the signal gets louder. The effect of this is to either yield more playing time or can be used to allow bigger transients without needing to uniformly space the pitch out to accommodate them.

Another technique is “Half Speed Mastering”. In the case of half-speed mastering, the whole process is slowed down to, you guessed it, half of the original speed. In other words, a typical 33 1/3 rpm record is cut at 16 2/3rpm. The source material is also slowed down (reducing the pitch in the process) meaning the final record will still sound normal when played back. The advantage with this technique is to drastically reduce the stress on the cutting head and stylus. At half speed, high frequencies will be cut far more accurately and big transients can be accommodated more easily.

Interestingly, since the mid-1970s, vinyl mastering houses began using digital delay lines instead of analogue delays on the signal going to the lathe. So even in the increasingly unlikely event that 100% of the recording, mixing and mastering was done entirely using analogue gear and media, the end of the vinyl mastering process may well have involved a conversion to digital and back to achieve half-speed mastering.

The Record Mastering Lathe

To the lathe itself. Simplistically, it can be seen as a thread cutting machine except the thread is a flat groove rather than a cylindrical one. Much has been written about these machines but the technology seems to have peaked with the Neumann VMS 80 paired with an SX-74 cutting head which was capable of DMM. Unsurprisingly, the manufacturing and development of lathes pretty much ceased after the arrival of the CD. Subsequently, top quality lathes like the Neumann command substantial prices when they (rarely) come up for sale. From the picture it’s possible to understand the way the cutting head moves in a linear fashion across the mastering medium. There is also a conventional tonearm on the machine and a microscope. The tone arm can be used to test a master if it’s DMM but lacquer masters have to be handled with extreme care and cannot be played. The final processes to produce a pressing master involves the metal plating of the lacquer master or a lacquer that has been lifted from a DMM master.

Finally, there is a vinyl LP record that can be shipped out and purchased by an eager punter but what are they getting? Are they getting a faithful recording of an artist or group? I would say no but it’s the best you can get if your medium is a vinyl LP record. The amount of processing and manipulation of the recorded sound to accommodate the limitations of vinyl are significant and will have limited a range of characteristics in the music being reproduced by the users equipment. High and low frequencies have had to be rolled off or limited so that they don’t ruin the master on the lathe. The RIAA curve has been applied at the lathe and then reversed in the phono preamp of the users equipment. Add this to the almost unlimited amount of manipulation that can be applied at the multi-track recording stage and it can be observed that there is an accumulation of processing in the end-to-end process. Vinyl has limited dynamic range, particularly when compared to digital recording methods. The practical dynamic range is normally somewhere between 20 and 40dB but some claim that it can be as high as 80dB but this is likely only under very specific circumstances as 80dB would take up a lot of room on the disc surface. By contrast, the dynamic range of a CD is 150dB without any special conditions needed. Opinions vary as to the actual frequency range of a vinyl LP. There are reports that they are capable of reproducing supersonic frequencies maybe as high as 100KHz. However, the high frequencies are a moot point as the RIAA preamp will only pass frequencies from 20Hz to 20KHz. The low end is less spectacular with a realistic threshold of around 24Hz. Finally, the last factor affecting the perceived stereo image is channel separation which generally gets worse at higher frequencies. The actual value is seldom more than around 20dB of separation and this value degrades with mistracking and incorrect stylus height/angle. Mistracking is inevitable in a pivoted arm as the master is cut with a linear mechanism. The closer the stylus gets to the centre of the LP, the bigger the tracking error. A linear tonearm will overcome this issue but as can be observed, there aren’t many of them due to the complicated nature of arranging a low friction linear mechanism which will allow the kind of mechanical properties needed for accurate tracking.

In addition to all of these defects, the actual frequency response of the listeners’ ears has a bearing on how the reproduced sound is perceived. If the listener is male and over 40 years old, it’s likely that the individuals’ ability to hear any frequency above 10 KHz is severely compromised.

At the end of the day, a vinyl record is a severely compromised form of recorded audio. The limitations on channel separation and dynamic range both conspire to reduce the psychological impression of a stereo image.

So how far should the end user go in the form of equipment and expense to listen to this medium? From what we have learned, the answer could be “go far enough so that the equipment doesn’t make the sound any worse” In which case it would be appropriate to look at factors that could make the sound worse.

Rumble.

Vinyl has inherent noise problems which the RIAA circuit attempts to mask but the playback device, in the form of a turntable, could actually add a signature of its own in the form of mechanical noise. Rumble is generated by the drive mechanism for the turntable and indicates low quality bearings in the platter spindle and possibly the motor. Some low cost turntables use a wheel with a rubber tire running on the rim of the platter for drive which will undoubtedly generate unwanted noise and vibrations. Excellent direct drive mechanisms have been designed over the years with one of the best being the Technics SP10 (SL-150 in HiFi form) which has excellent speed stability and extremely low rumble at -70dB, well below any that would be generated by the disc itself. The current audiophile seems to favour belt drive as almost all “High End” turntables are driven this way. Belt drive is inferior to a well-designed direct drive but it’s simple and potentially adds some mechanical isolation between the drive motor and the platter.

Mistracking.

As previously described, using a pivot style tonearm will inevitably cause tracking error towards the centre of the record. The only remedy to this is an effective linear tracking tonearm.

Wow and Flutter.

Once again this is down to the drive mechanism on the platter. To counter this the platter needs to have an adequate amount of weight to achieve a stable speed by dint of the flywheel effect, where the inertia of the rotating platter stores some energy and will tend to flatten out any cogging from the drive mechanism. A direct drive platter is more like the rotating element of an AC motor and can achieve very stable speed by the application of a multi-phase AC drive circuit.

Isolation.

The turntable should have some way to resist or damp out external vibration especially low frequency energy that can be generated by the speakers themselves. In extreme situations, a positive feedback loop can get established that will adversely affect the playback.

Based on all of these factors, what then constitutes a device which will spin a vinyl disc at 33.333rpm and not add any unwanted elements? There are probably quite a lot of turntables that would cover the brief. One that springs to mind is the Rega Planar. Despite its modest price, it’s built with high quality components and will allow a user to play a vinyl disc as accurately as is possible with a pivoting tonearm.

Little more can be gained in the form of reproduction by drastically increasing the weight or mechanical complexity of the turntable especially when that specification would actually exceed that of the disc lathe that created the master.

Don’t forget, the reproduction equipment cant put back what is missing from the disc mastering process. Speaking of which, due to the the amount of missing and compromised information on an LP, it can’t really be considered “HiFi” in the current era. Compared to the excellent capabilities of digital recording, especially in the area of dynamic range, noise, wow & flutter and accuracy, a vinyl LP and it’s playing method is thoroughly primitive.

Last edited: