Punter

Active Member

- Joined

- Jul 19, 2022

- Messages

- 241

- Likes

- 1,173

By the end of the 80’s it was obvious that conventional reel to reel audio tape was pretty much dead as a domestic music format. What was a more than competitive technology in the 60’s and 70’s with respect to fidelity had morphed into the compact cassette but that wasn’t enough to save tape. Cassettes were convenient but the shortcomings of putting four tracks on a tiny 0.15 inch (3.81 mm) polymer tape were known to anyone who used them. This didn’t prevent the Compact Cassette becoming a very significant music format which was only made redundant by the proliferation of the Compact Disc. To find out why tape failed as a music playback format, we have to go back in time and explore the primitive reel to reel technology that existed pre WWII.

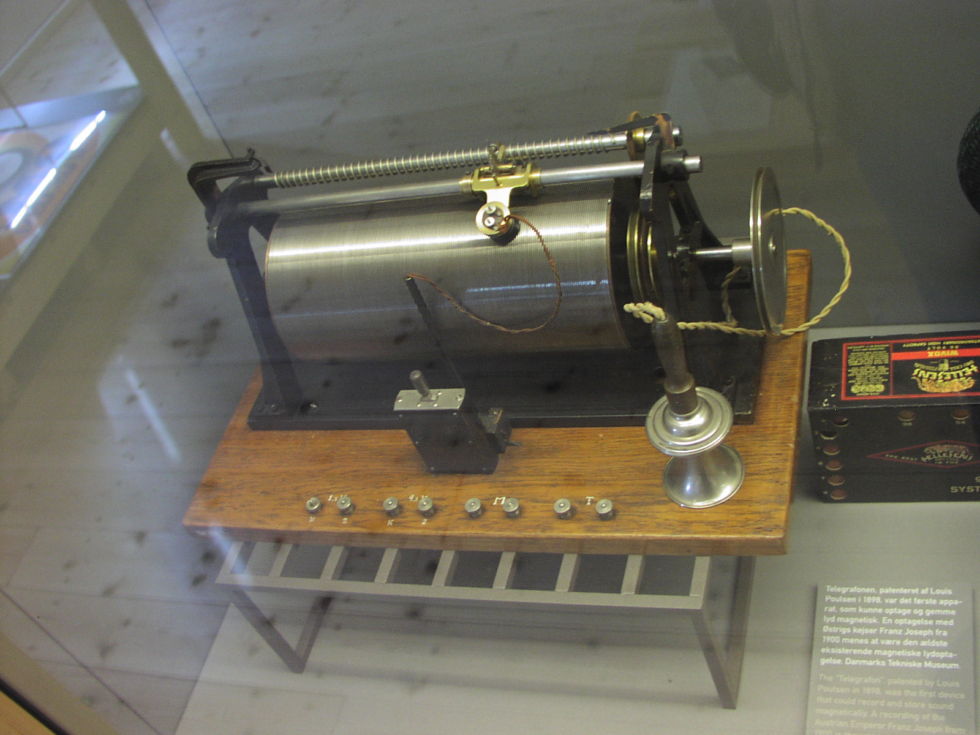

The first viable reel to reel format was the magnetic wire recorder. Invented 1898 and patented two years later, the device was invented by Valdemar Poulsen, a Danish-American inventor who dubbed it the "Telegraphone". The device was somewhat crude, but it did have the key elements: a metal wire was pulled between spools across a recording head, which magnetised the wire in accordance with the sound signal it was receiving at that moment. The wire could then be rewound and played back via the head which made it the first device that could exceed a couple of minutes continuous recording. The primary downside to this method of recording was that the recorded audio spectrum was quite narrow and not really suited to anything other than recording the human voice.

A company was formed around the invention and The American Telegraphone Company then began manufacturing machines, which, in terms of audio quality, were superior to their only rival, the wax cylinder. Another advantage was the wire reels could be used and reused time and time again and were capable of recording for far longer. Primarily used as dictation machines, wire recorder sales were steady but not spectacular, it was not a machine most businesses could afford. The use of wire recorders for the purpose of capturing music wasn’t practical until after WWII when the use of first DC bias and then AC bias was applied to the recording process.

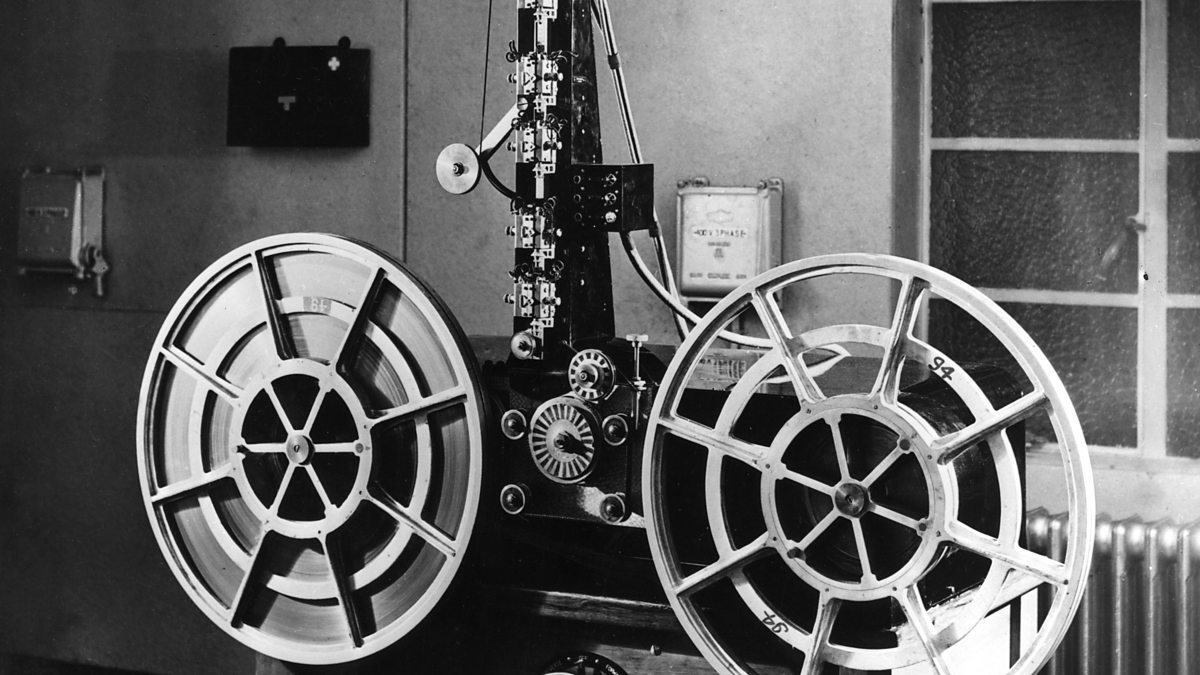

Another reel to reel recording system that was in development in parallel to the wire recorder was the metal tape recorder. Dr. Kurt Stille was involved in commercialising the wire recorder for the Vox company in Germany when he developed a larger format machine using a metal ribbon or tape in place of the wire. This development was noticed by film producer and showman Louis Blattner who was looking for a way to synchronise audio with film. This was the birth of the “Blattnerphone” and one of the first customers was the BBC. In September 1930 a machine was installed for trials at Avenue House, then the home of the BBC's Research Department and the results were deemed good enough for speech, but not for music.

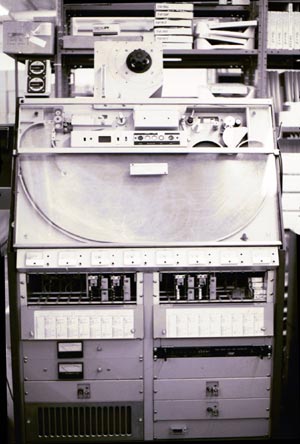

The BBC negotiated a five-year rental agreement with the British Blattnerphone Company in January 1931 at £500 for the first year, £1000 per year thereafter, plus £250 for each additional machine. The Blattnerphone was an imposing unit with two reels of 6mm metal tape on horizontally opposed reels which ran at 5ft/sec. A full spool weighing 21lbs contained just over a mile of tape giving a recording time of twenty minutes. The speed of the D.C. motor had to be controlled by watching a stroboscope attached to the capstan and operating a sliding rheostat. The machines soon proved to be mechanically unreliable. This unreliability was primarily connected to tape speed control. Each reel had its own DC motor and no technology existed at the time to control the motor speeds accurately. Another major issue with these machines was head wear. A metal tape dragging across another metal surface was a formula for abrasion and the BBC Blattnerphones dealt with this by having five heads fitted to the machine. As one wore out, another could be brought into play to allow the machine to continue operating.

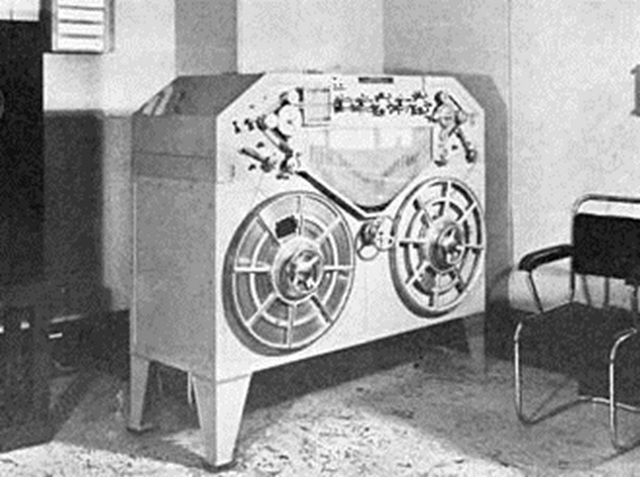

The BBC continued to use the Blattnerphone machines with a subsequent model being set up for 3mm tape. However the operational issues were not resolved until Blattnerphone was bought out by Marconi in 1933 and developed the Marconi-Stille machine which had many improvements over the original machines. To help stabilise the tape speed and general reliability, a tape “reservoir” was incorporated into the machine so that the supply and take-up motors had less influence over tape speed. The left hand reel fed into the reservoir chamber and the right hand reel pulled it out, regulated by the capstan. These machines continued in service with the BBC until after WWII. Another aspect of operating these machines was the tape itself. The metal ribbon had to be handled very carefully as the edges were sharp enough to inflict a cut, most operators wore leather gloves when threading the machines or handling tape. Caution also had to be taken when a tape broke. Operators knew to stay clear of the flailing ends of the tape until the machine was stopped. The quality of audio was steadily improved by the use of DC then AC bias on the record heads but the metal ribbon machines never achieved music level fidelity.

Meanwhile, in Germany, the AEG Company in collaboration with BASF was developing a new kind of tape. It was a polymer ribbon coated with carbonyl iron powder which had originally been produced to make inductors for telephones. The first 50,000 meters of magnetic audio tape were supplied to the AEG electronics corporation in 1934. A year later, AEG presented the first polymer tape recorder to the public at the Berlin Radio Fair in 1935. The original units would still be classified as low fi, using DC tape bias but continued development saw the introduction of high frequency AC tape bias. By 1941 AEG hi-fi Magnetophons were in service in radio stations all over Germany. The AC bias machines were unknown to Allied countries until a chance discovery by a Major Mullin in the U.S. Army Signal Corps on a spring night in England in 1944

Mullin graduated from the University of Santa Clara with a B.S. in electrical engineering in 1937, then worked for Pacific Telephone and Telegraph in San Francisco until the war started. By 1944, he had attained the rank of Major and was attached to the RAF's radar research labs in Farnborough, England.

While working late one night, Mullin was happy to find something pleasant playing on the radio for company — the Berlin Philharmonic playing Beethoven's Ninth Symphony on Radio Berlin. But Mullin was mystified: The performance's fidelity was far too good to be a 16-inch wax disc recording. In addition, there were no breaks every 15 minutes to change discs, Mullin figured it had to be a live broadcast. But it couldn't be — if it was 2 am in London, it was 3 am in Berlin. Mullin was right — the orchestra wasn’t up late, it was a recording but not the usual kind, which is why Mullin was confused. This encounter left an indelible impression on Mullin and fortunately for him (and the home media industry) he was given an opportunity to pursue this mystery after WWII ended.

After the war, Mullin was assigned to the Technical Liaison Division of the Signal Corps in Paris. The task of this division was to discover what the Germans had been working on in communications. They were to investigate all technologies, radio, radar, wireless, telegraph and teletype. Mullin ended up in Frankfurt on one such expedition. There he encountered a British officer, who told him about a new type of recorder discovered at a Radio Frankfurt station in Bad Nauheim. This was not a standard DC biased tape machine but an AC biased machine. Mullin didn't exactly believe the report — he had encountered dozens of low-fi DC bias recorders all over Germany. At this point in his expedition, he could have returned to Paris but the promise of a hi-fi tape recorder was too good to pass up.

To his delight, at Bad Nauheim he found four hi-fi Magnetophons and 50 reels of red oxide BASF tape. He tinkered with them a bit back in Paris and made a report to the Army. Understanding the significance of the machines, he packed up two of them and sent them to his home in San Francisco as souvenirs of war (serviceman could take almost anything that was not deemed to be of significant value). He also sent himself the 50 reels of tape.

When Mullin returned home, he started tinkering to improve the Magnetophons. On May 16, 1946, Mullin stunned attendees at the annual Institute of Radio Engineers (IRE) conference in San Francisco by switching between a concealed live jazz combo and a recording, literally asking the question "Is it live or a recording?" None of the golden ears in the audience could tell. It was the first public demonstration of hi-fi audio tape recording in America.

News travelled fast and one of the first parties to become interested in the Magnetophon was the engineering team of Bing Crosby. Crosby hated doing live radio. He also hated recording his shows on wax records because they sounded terrible to the aural perfectionist. When Crosby's engineers heard about Mullin and his Magnetophons, they quickly hired him and his machine. In August 1947, Crosby became the first performer to record a radio program on tape; the show was broadcast on October 1 1947.

Crosby wasn't the only one interested in Mullin's Magnetophons. In Redwood City California, a small company called Ampex was looking for something to replace the radar gear they'd been producing for the government. Ampex hooked up with Mullin and, by April 1948, they brought the first commercially available audio tape recorder to market, the Ampex Model 200. Bing Crosby purchased a major financial stake in Ampex and actively promoted the machines and technology. Crosby even gave an Ampex Model 200 to Les Paul in 1948. Les, an inveterate tinkerer and inventor, modified it by adding an extra head, which permitted him to pick up the sound off the tape before the tape was erased, and bring it back through the machine and record another track added to what was previously on the tape. This led to the advent of many tape techniques used in music recording and ultimately to the development of true multi-track machines.

I have mentioned tape “bias” a few times so this might be an opportune moment to explain it. Bias is important because it’s inclusion in the tape recording process allowed recordings to go full bandwidth or hi-fi. The original electromagnetic recorders, both wire and metal tape, did not have bias as part of the recording process. Subsequently, the recordings were of limited bandwidth and a very weak magnetic signature on the medium. These limitations were the result of the magnetic properties of the tape or wire. These physical limitations are magnetic coercivity, magnetic permeability which combine to form the magnetic hysteresis of the medium. The original attempt at biasing was to use a DC current to apply a standing magnetic force on the wire or tape which would have the input signal superimposed on it. DC bias improved the recording quality by creating a homogenous magnetic state on the medium which the input signal could be imprinted on. Bias also acts to erase the magnetic state of the tape as the recording progresses, without which, there could be remnants of previous recordings or random magnetic states which could cause distortion.

High frequency AC bias was superior to DC bias because the effect of AC bias is to “stir” the magnetic medium in such a way as to reduce the effect of hysteresis. Hysteresis in a magnetic recording medium relates directly to its ability to be imprinted with a magnetic state, the higher the frequency, the more the medium resists being magnetised. Bias sinewave drives the magnetic media through it’s positive and negative (north / south) hysteresis loop in such a way that the audio signal can more easily imprint on the medium. With the bias set at the correct frequency and level for the medium, it can be optimised for full bandwidth recording. The German polymer tape with the oxide coating was superior to both wire and metal ribbon in both coercivity and permeability which made the hysteresis less resistant and subsequently allowed higher audio frequencies to be imprinted on the tape. AC bias improved the wire and metal ribbon formats but they never topped BASF tape. The remaining source of distortion for magnetic tape is “saturation” where the input signal amplitude exceeds the ability of the tape to accept the magnetic coercion. In other words, the tape “tops out” and the signal squares off.

While we’re on technical matters it might be worthwhile having a look at some of the finer points of a tape mechanism and some other details.

Tape: As previously mentioned, conventional recording tape is a polymer ribbon coated with carbonyl iron powder. Later on, chromium oxide was added to the mix to improve the tapes ability to record higher audio frequencies which was known as “chrome” tape. Early machines used “platters” of tape rather than reels, especially on smaller machines. The platters dictated that the machine deck was horizontal and this was the common configuration of reel to reel machines moving into the 50’s and further. Vertical machines had the tape on reels as we know them, the early German Magnetophons that were used for long recordings were configured this way. Of course, eventually, platter tape was discarded and tape was universally on reels except in Russia where they were still using recorders copied from the original Magnetophon in radio stations, all the way into the 80’s. Further development added a back coating to the tape which aided packing on the reels and reduced magnetic “print-through” where the recorded signal would transfer to the tape opposite it on the reel and cause an audible “pre-echo” on playback.

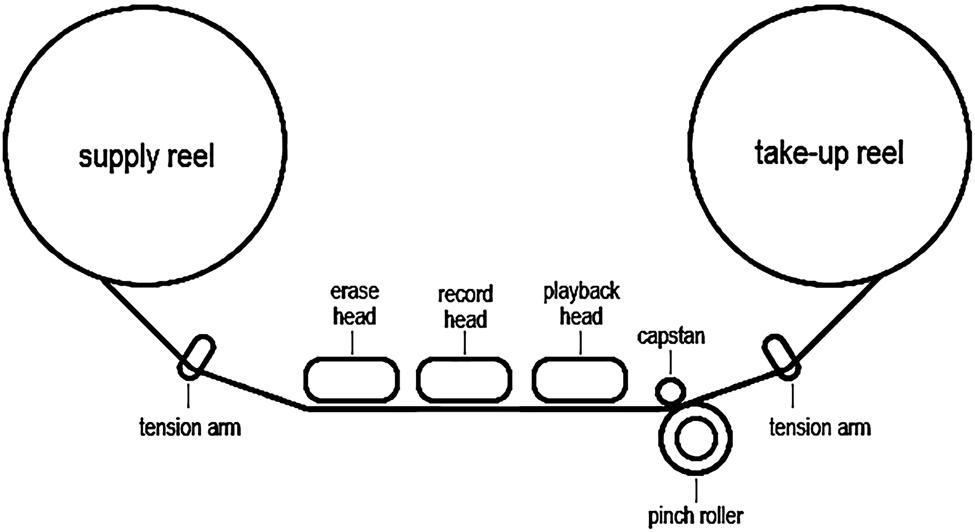

Transport: The tape transport was one of the biggest headaches in early machines. The difficulty of using valve electronics and valve-based oscillators for speed control was problematic right up to the advent of the Marconi-Stille units while not perfect, were a big improvement over the Blattnerphone machines. The Magnetophon, again, led the way as far as a stable mechanism was concerned. All subsequent machines from Ampex and others owed a lot to the German engineers who designed it. The transport itself comprises of an almost universal set of components. The supply and take-up reels, left to right are pretty self-explanatory, these are usually flanked by guide rollers which are on sprung arms to provide stable lateral tracking and a small amount of reserve tension which assists with speed stability. Between these arrangements are the heads with the erase, record and playback heads from left to right. Early machines and low cost machines sometimes had a passive magnet as an erase head or skipped it all together and relied on bias on the record head to erase the tape as it recorded. A later addition to transports was a tachometer wheel on the take-up side and “tape lifts” which were a pair of pins that were employed when rewinding or fast-forwarding the tape. The lifts moved the tape away from the heads to prevent accelerated wear from these operations.

So the stage is set for tape to become the dominant hi-fi format yes? Well no actually. While the reel to reel has found a home in just about every studio and radio station, it hadn’t really permeated the domestic market, especially in the late 40’s and early 50’s. The first machines that came on the market were largely layback machines (where the reels are horizontal). An example of the 50’s machines was the British Emicorder, manufactured by EMI, which used valve electronics. The Emicorder was unusual in that the right hand or take-up reel rotated in the same direction as the supply reel. This meant that the machine had to be laced with the tape entering the take-up spool from the right side and wrapping clockwise. The other practical upshot of this was that the operator had to add a twist to the tape if it was a half-track mono recording so that the tracks would end up on the correct side if the take-up spool was flipped to the supply side.

Not all the machines available in this era had a similar quirk, indeed this machine was somewhat unusual. For the most part, machines had the supply and take-up reels running in the conventional way, both running CCW. As part of a domestic sound system, reel to reel machines were around the top end of cost and only the well-heeled would have included one in their setup.

The advent of the transistor revolutionised consumer electronics and the effect on the domestic reel to reel machine was no exception. In short order, the reel to reel morphed from a professional/ prosumer device to an accessible product for a wide range of consumers. A multitude of machines came on the market, all with pretty much the same layback layout. While there were a plethora of American and British manufacturers, the Japanese also had a stake in the market with brands like Sony and National. To cut costs, some of the lower priced machines would play back a stereo tape but only record in mono. It’s difficult to know exactly how people were using their tape recorders but it’s likely they actually made more frequent use of the recording ability of the machine rather than using it as a source of music or entertainment.

Compared to the abundance of titles available on 78’s and later, LP’s, pre-recorded tapes were in relatively short supply. EMI began selling dual mono tapes in 1949 in the US with a scant ten titles or so. RCA Victor joined in by 1954 with stereo offerings. Despite their being a reasonable catalogue of titles, pre-recorded tapes were more expensive than LP’s and sales were slow. The stereo tapes were recorded at 7.1/2ips which was considered to be the domestic hi-fi standard tape speed but as time went by and sales were being easily outstripped by vinyl, EMI began offering tapes with the equivalent of two albums per unit but dropped the tape speed to 3.3/4ips with a subsequent drop in audio quality.

Moving into the 70’s the reel to reel became a hi-fi component and looked more like a professional upright deck. In fact, having a reel to reel in your setup made you look “serious” about your system. Brands that came to the fore now were Akai and Kenwood, with the tape deck styled to integrate into the system as a component. Regardless, reel to reel was still not where it wanted to be in the hi-fi universe. Compared to LP’s, the catalogue was still limited and there was a threat looming which would pretty much kill off the domestic reel to reel.

Reel to reel tape, while it offered potentially better music reproduction than LP’s never supplanted vinyl. Compared to putting on a record, reel to reels had to be loaded and threaded before playing. Reel to reel decks needed maintenance too, head, capstan and pinch wheel cleaning had to be carried out regularly. Even though there were numerous machines and manufacturers, the market for tape machines was never on the scale of turntables which were substantially simpler and cheaper. After limping along for a decade and a half, the market for pre-recorded reel-to-reel tapes fell off a cliff around the time competitive cassette players were introduced.

The compact cassette began life as a convenient tape format for low-cost portable recorders, much like the early transistor electronic tape machines of the 1950’s and 60’s. Invented by Lou Ottens and his team at the Dutch company Philips in 1963, the compact cassette was originally intended for dictation machines (where have I heard that before?). However, Sony put pressure on Philips to license the design to them for free and following that, cassette machines began their journey to become a globally ubiquitous music format. 1973 -1974 saw several innovations that allowed cassettes to offer similar sound quality to open-reel decks — Dolby noise reduction, three-head decks and chrome tape. Background noise and hiss were reduced to levels most listeners could accept. The convenience of the cassette tape and the improved tape chemistry saw it become a standard hi-fi component. Record labels got on board completely with the cassette. Compared to the lukewarm uptake of open reel tape, the convenience of the cassette and the lower cost of duplication resulted in an almost 1:1 ratio of LP to Cassette catalogues.

Speaking of duplication, the process for duplicating pre-recorded reel to reel tape was a far more complex and expensive exercise than pressing an LP and another reason that the range of titles available was limited. The process involved master, slave and transfer decks and the process to cut and individually wind tapes for final packaging. The process started with a master deck running a master tape. However, the master tape was not on a reel but stored in a tape reservoir similar to that on the Marconi-Stille recorder.

The master was spliced end to end to create a loop which would only be run forward. The master tapes were mostly duplicated direct from studio master tapes but sometimes they were created from an LP! The slave decks were loaded with blank tape 6000-8000 feet in length which was recorded and re-reeled onto a precision reusable reel. It was then mounted onto transfer machines that would wind the tape onto individual "consumer" reels that the operators would mount into the machine one-at-a-time. To add a modicum of automation to this process, there were pilot tones added to the bulk recorded tape which would signal the transfer deck to stop at the end of the recording. The machine would transfer the recorded tape until it encountered the pilot tones, then stop and back up until they were found again. The operator would then splice on a length of leader, splice a leader onto the start of the next recording, change the output reel and go again. These machines ran at very high speeds and used pneumatic disc brakes to stop the reels. The individual reel of tape was then labelled, boxed, and packed. A QC team would sample the duplicates on a random basis, listening to the entire tape to detect defects which would indicate problems with the slave recorders or transfer decks.

It’s no wonder that the cassette became the dominant tape format. Running an open reel duplication plant would have been a maintenance nightmare as well as being highly labour intensive. Cassette duplication, by contrast, was infinitely simpler.

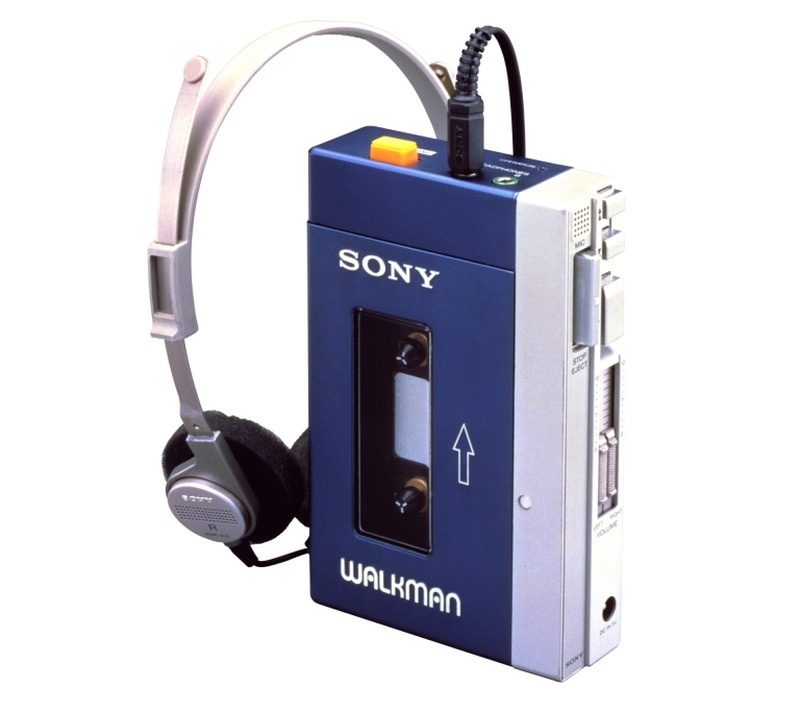

The final nail in the coffin was the advent of the Walkman. Without any doubt, the cassette was the shizz and kicked off a personal music culture which eventually morphed into the iPod and then streaming audio via mobile phone. How many of us made our own mix tapes from our LP collection to listen to on the move either in a portable player or in the car?

These days, reel to reel hi-fi is very much a fringe pursuit and the cost of pre-recorded tapes either vintage or new duplicates prices and quality vary wildly. In addition to that, unlike a vintage vinyl record, tape degrades or “perishes” over time as the oxide and back coatings break down chemically. Even tapes stored in humidity controlled rooms suffer this fate. Tape restoration by baking is possible but this often results in a tape that can be played once or twice before the oxide layer breaks down terminally. Also, the longer a tape is stored, the greater the problem with print through. Add to this the inevitable problems with servicing complex machines that have been out of production for over twenty years and it’s obvious that it’s a pursuit for dedicated enthusiasts.

I haven’t dipped into the many other uses of magnetic media in this article. In truth, Ampex was developing tape recorders for video in parallel with audio machines. The technology developed to accurately and reliably record a big fat video signal was quite astounding with rotary heads and tape riding on a cushion of air to reduce wear and overall tape-path friction. Add to that the many uses of magnetic tape for data storage and its plain that those original AEG/BASF machines were massively significant to the development of computer technology as well as audio and video.

The first viable reel to reel format was the magnetic wire recorder. Invented 1898 and patented two years later, the device was invented by Valdemar Poulsen, a Danish-American inventor who dubbed it the "Telegraphone". The device was somewhat crude, but it did have the key elements: a metal wire was pulled between spools across a recording head, which magnetised the wire in accordance with the sound signal it was receiving at that moment. The wire could then be rewound and played back via the head which made it the first device that could exceed a couple of minutes continuous recording. The primary downside to this method of recording was that the recorded audio spectrum was quite narrow and not really suited to anything other than recording the human voice.

A company was formed around the invention and The American Telegraphone Company then began manufacturing machines, which, in terms of audio quality, were superior to their only rival, the wax cylinder. Another advantage was the wire reels could be used and reused time and time again and were capable of recording for far longer. Primarily used as dictation machines, wire recorder sales were steady but not spectacular, it was not a machine most businesses could afford. The use of wire recorders for the purpose of capturing music wasn’t practical until after WWII when the use of first DC bias and then AC bias was applied to the recording process.

Another reel to reel recording system that was in development in parallel to the wire recorder was the metal tape recorder. Dr. Kurt Stille was involved in commercialising the wire recorder for the Vox company in Germany when he developed a larger format machine using a metal ribbon or tape in place of the wire. This development was noticed by film producer and showman Louis Blattner who was looking for a way to synchronise audio with film. This was the birth of the “Blattnerphone” and one of the first customers was the BBC. In September 1930 a machine was installed for trials at Avenue House, then the home of the BBC's Research Department and the results were deemed good enough for speech, but not for music.

The BBC negotiated a five-year rental agreement with the British Blattnerphone Company in January 1931 at £500 for the first year, £1000 per year thereafter, plus £250 for each additional machine. The Blattnerphone was an imposing unit with two reels of 6mm metal tape on horizontally opposed reels which ran at 5ft/sec. A full spool weighing 21lbs contained just over a mile of tape giving a recording time of twenty minutes. The speed of the D.C. motor had to be controlled by watching a stroboscope attached to the capstan and operating a sliding rheostat. The machines soon proved to be mechanically unreliable. This unreliability was primarily connected to tape speed control. Each reel had its own DC motor and no technology existed at the time to control the motor speeds accurately. Another major issue with these machines was head wear. A metal tape dragging across another metal surface was a formula for abrasion and the BBC Blattnerphones dealt with this by having five heads fitted to the machine. As one wore out, another could be brought into play to allow the machine to continue operating.

The BBC continued to use the Blattnerphone machines with a subsequent model being set up for 3mm tape. However the operational issues were not resolved until Blattnerphone was bought out by Marconi in 1933 and developed the Marconi-Stille machine which had many improvements over the original machines. To help stabilise the tape speed and general reliability, a tape “reservoir” was incorporated into the machine so that the supply and take-up motors had less influence over tape speed. The left hand reel fed into the reservoir chamber and the right hand reel pulled it out, regulated by the capstan. These machines continued in service with the BBC until after WWII. Another aspect of operating these machines was the tape itself. The metal ribbon had to be handled very carefully as the edges were sharp enough to inflict a cut, most operators wore leather gloves when threading the machines or handling tape. Caution also had to be taken when a tape broke. Operators knew to stay clear of the flailing ends of the tape until the machine was stopped. The quality of audio was steadily improved by the use of DC then AC bias on the record heads but the metal ribbon machines never achieved music level fidelity.

Meanwhile, in Germany, the AEG Company in collaboration with BASF was developing a new kind of tape. It was a polymer ribbon coated with carbonyl iron powder which had originally been produced to make inductors for telephones. The first 50,000 meters of magnetic audio tape were supplied to the AEG electronics corporation in 1934. A year later, AEG presented the first polymer tape recorder to the public at the Berlin Radio Fair in 1935. The original units would still be classified as low fi, using DC tape bias but continued development saw the introduction of high frequency AC tape bias. By 1941 AEG hi-fi Magnetophons were in service in radio stations all over Germany. The AC bias machines were unknown to Allied countries until a chance discovery by a Major Mullin in the U.S. Army Signal Corps on a spring night in England in 1944

Mullin graduated from the University of Santa Clara with a B.S. in electrical engineering in 1937, then worked for Pacific Telephone and Telegraph in San Francisco until the war started. By 1944, he had attained the rank of Major and was attached to the RAF's radar research labs in Farnborough, England.

While working late one night, Mullin was happy to find something pleasant playing on the radio for company — the Berlin Philharmonic playing Beethoven's Ninth Symphony on Radio Berlin. But Mullin was mystified: The performance's fidelity was far too good to be a 16-inch wax disc recording. In addition, there were no breaks every 15 minutes to change discs, Mullin figured it had to be a live broadcast. But it couldn't be — if it was 2 am in London, it was 3 am in Berlin. Mullin was right — the orchestra wasn’t up late, it was a recording but not the usual kind, which is why Mullin was confused. This encounter left an indelible impression on Mullin and fortunately for him (and the home media industry) he was given an opportunity to pursue this mystery after WWII ended.

After the war, Mullin was assigned to the Technical Liaison Division of the Signal Corps in Paris. The task of this division was to discover what the Germans had been working on in communications. They were to investigate all technologies, radio, radar, wireless, telegraph and teletype. Mullin ended up in Frankfurt on one such expedition. There he encountered a British officer, who told him about a new type of recorder discovered at a Radio Frankfurt station in Bad Nauheim. This was not a standard DC biased tape machine but an AC biased machine. Mullin didn't exactly believe the report — he had encountered dozens of low-fi DC bias recorders all over Germany. At this point in his expedition, he could have returned to Paris but the promise of a hi-fi tape recorder was too good to pass up.

To his delight, at Bad Nauheim he found four hi-fi Magnetophons and 50 reels of red oxide BASF tape. He tinkered with them a bit back in Paris and made a report to the Army. Understanding the significance of the machines, he packed up two of them and sent them to his home in San Francisco as souvenirs of war (serviceman could take almost anything that was not deemed to be of significant value). He also sent himself the 50 reels of tape.

When Mullin returned home, he started tinkering to improve the Magnetophons. On May 16, 1946, Mullin stunned attendees at the annual Institute of Radio Engineers (IRE) conference in San Francisco by switching between a concealed live jazz combo and a recording, literally asking the question "Is it live or a recording?" None of the golden ears in the audience could tell. It was the first public demonstration of hi-fi audio tape recording in America.

News travelled fast and one of the first parties to become interested in the Magnetophon was the engineering team of Bing Crosby. Crosby hated doing live radio. He also hated recording his shows on wax records because they sounded terrible to the aural perfectionist. When Crosby's engineers heard about Mullin and his Magnetophons, they quickly hired him and his machine. In August 1947, Crosby became the first performer to record a radio program on tape; the show was broadcast on October 1 1947.

Crosby wasn't the only one interested in Mullin's Magnetophons. In Redwood City California, a small company called Ampex was looking for something to replace the radar gear they'd been producing for the government. Ampex hooked up with Mullin and, by April 1948, they brought the first commercially available audio tape recorder to market, the Ampex Model 200. Bing Crosby purchased a major financial stake in Ampex and actively promoted the machines and technology. Crosby even gave an Ampex Model 200 to Les Paul in 1948. Les, an inveterate tinkerer and inventor, modified it by adding an extra head, which permitted him to pick up the sound off the tape before the tape was erased, and bring it back through the machine and record another track added to what was previously on the tape. This led to the advent of many tape techniques used in music recording and ultimately to the development of true multi-track machines.

I have mentioned tape “bias” a few times so this might be an opportune moment to explain it. Bias is important because it’s inclusion in the tape recording process allowed recordings to go full bandwidth or hi-fi. The original electromagnetic recorders, both wire and metal tape, did not have bias as part of the recording process. Subsequently, the recordings were of limited bandwidth and a very weak magnetic signature on the medium. These limitations were the result of the magnetic properties of the tape or wire. These physical limitations are magnetic coercivity, magnetic permeability which combine to form the magnetic hysteresis of the medium. The original attempt at biasing was to use a DC current to apply a standing magnetic force on the wire or tape which would have the input signal superimposed on it. DC bias improved the recording quality by creating a homogenous magnetic state on the medium which the input signal could be imprinted on. Bias also acts to erase the magnetic state of the tape as the recording progresses, without which, there could be remnants of previous recordings or random magnetic states which could cause distortion.

High frequency AC bias was superior to DC bias because the effect of AC bias is to “stir” the magnetic medium in such a way as to reduce the effect of hysteresis. Hysteresis in a magnetic recording medium relates directly to its ability to be imprinted with a magnetic state, the higher the frequency, the more the medium resists being magnetised. Bias sinewave drives the magnetic media through it’s positive and negative (north / south) hysteresis loop in such a way that the audio signal can more easily imprint on the medium. With the bias set at the correct frequency and level for the medium, it can be optimised for full bandwidth recording. The German polymer tape with the oxide coating was superior to both wire and metal ribbon in both coercivity and permeability which made the hysteresis less resistant and subsequently allowed higher audio frequencies to be imprinted on the tape. AC bias improved the wire and metal ribbon formats but they never topped BASF tape. The remaining source of distortion for magnetic tape is “saturation” where the input signal amplitude exceeds the ability of the tape to accept the magnetic coercion. In other words, the tape “tops out” and the signal squares off.

While we’re on technical matters it might be worthwhile having a look at some of the finer points of a tape mechanism and some other details.

Tape: As previously mentioned, conventional recording tape is a polymer ribbon coated with carbonyl iron powder. Later on, chromium oxide was added to the mix to improve the tapes ability to record higher audio frequencies which was known as “chrome” tape. Early machines used “platters” of tape rather than reels, especially on smaller machines. The platters dictated that the machine deck was horizontal and this was the common configuration of reel to reel machines moving into the 50’s and further. Vertical machines had the tape on reels as we know them, the early German Magnetophons that were used for long recordings were configured this way. Of course, eventually, platter tape was discarded and tape was universally on reels except in Russia where they were still using recorders copied from the original Magnetophon in radio stations, all the way into the 80’s. Further development added a back coating to the tape which aided packing on the reels and reduced magnetic “print-through” where the recorded signal would transfer to the tape opposite it on the reel and cause an audible “pre-echo” on playback.

Transport: The tape transport was one of the biggest headaches in early machines. The difficulty of using valve electronics and valve-based oscillators for speed control was problematic right up to the advent of the Marconi-Stille units while not perfect, were a big improvement over the Blattnerphone machines. The Magnetophon, again, led the way as far as a stable mechanism was concerned. All subsequent machines from Ampex and others owed a lot to the German engineers who designed it. The transport itself comprises of an almost universal set of components. The supply and take-up reels, left to right are pretty self-explanatory, these are usually flanked by guide rollers which are on sprung arms to provide stable lateral tracking and a small amount of reserve tension which assists with speed stability. Between these arrangements are the heads with the erase, record and playback heads from left to right. Early machines and low cost machines sometimes had a passive magnet as an erase head or skipped it all together and relied on bias on the record head to erase the tape as it recorded. A later addition to transports was a tachometer wheel on the take-up side and “tape lifts” which were a pair of pins that were employed when rewinding or fast-forwarding the tape. The lifts moved the tape away from the heads to prevent accelerated wear from these operations.

So the stage is set for tape to become the dominant hi-fi format yes? Well no actually. While the reel to reel has found a home in just about every studio and radio station, it hadn’t really permeated the domestic market, especially in the late 40’s and early 50’s. The first machines that came on the market were largely layback machines (where the reels are horizontal). An example of the 50’s machines was the British Emicorder, manufactured by EMI, which used valve electronics. The Emicorder was unusual in that the right hand or take-up reel rotated in the same direction as the supply reel. This meant that the machine had to be laced with the tape entering the take-up spool from the right side and wrapping clockwise. The other practical upshot of this was that the operator had to add a twist to the tape if it was a half-track mono recording so that the tracks would end up on the correct side if the take-up spool was flipped to the supply side.

Not all the machines available in this era had a similar quirk, indeed this machine was somewhat unusual. For the most part, machines had the supply and take-up reels running in the conventional way, both running CCW. As part of a domestic sound system, reel to reel machines were around the top end of cost and only the well-heeled would have included one in their setup.

The advent of the transistor revolutionised consumer electronics and the effect on the domestic reel to reel machine was no exception. In short order, the reel to reel morphed from a professional/ prosumer device to an accessible product for a wide range of consumers. A multitude of machines came on the market, all with pretty much the same layback layout. While there were a plethora of American and British manufacturers, the Japanese also had a stake in the market with brands like Sony and National. To cut costs, some of the lower priced machines would play back a stereo tape but only record in mono. It’s difficult to know exactly how people were using their tape recorders but it’s likely they actually made more frequent use of the recording ability of the machine rather than using it as a source of music or entertainment.

Compared to the abundance of titles available on 78’s and later, LP’s, pre-recorded tapes were in relatively short supply. EMI began selling dual mono tapes in 1949 in the US with a scant ten titles or so. RCA Victor joined in by 1954 with stereo offerings. Despite their being a reasonable catalogue of titles, pre-recorded tapes were more expensive than LP’s and sales were slow. The stereo tapes were recorded at 7.1/2ips which was considered to be the domestic hi-fi standard tape speed but as time went by and sales were being easily outstripped by vinyl, EMI began offering tapes with the equivalent of two albums per unit but dropped the tape speed to 3.3/4ips with a subsequent drop in audio quality.

Moving into the 70’s the reel to reel became a hi-fi component and looked more like a professional upright deck. In fact, having a reel to reel in your setup made you look “serious” about your system. Brands that came to the fore now were Akai and Kenwood, with the tape deck styled to integrate into the system as a component. Regardless, reel to reel was still not where it wanted to be in the hi-fi universe. Compared to LP’s, the catalogue was still limited and there was a threat looming which would pretty much kill off the domestic reel to reel.

Reel to reel tape, while it offered potentially better music reproduction than LP’s never supplanted vinyl. Compared to putting on a record, reel to reels had to be loaded and threaded before playing. Reel to reel decks needed maintenance too, head, capstan and pinch wheel cleaning had to be carried out regularly. Even though there were numerous machines and manufacturers, the market for tape machines was never on the scale of turntables which were substantially simpler and cheaper. After limping along for a decade and a half, the market for pre-recorded reel-to-reel tapes fell off a cliff around the time competitive cassette players were introduced.

The compact cassette began life as a convenient tape format for low-cost portable recorders, much like the early transistor electronic tape machines of the 1950’s and 60’s. Invented by Lou Ottens and his team at the Dutch company Philips in 1963, the compact cassette was originally intended for dictation machines (where have I heard that before?). However, Sony put pressure on Philips to license the design to them for free and following that, cassette machines began their journey to become a globally ubiquitous music format. 1973 -1974 saw several innovations that allowed cassettes to offer similar sound quality to open-reel decks — Dolby noise reduction, three-head decks and chrome tape. Background noise and hiss were reduced to levels most listeners could accept. The convenience of the cassette tape and the improved tape chemistry saw it become a standard hi-fi component. Record labels got on board completely with the cassette. Compared to the lukewarm uptake of open reel tape, the convenience of the cassette and the lower cost of duplication resulted in an almost 1:1 ratio of LP to Cassette catalogues.

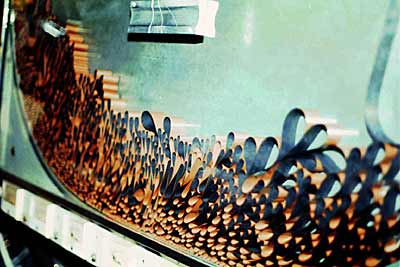

Speaking of duplication, the process for duplicating pre-recorded reel to reel tape was a far more complex and expensive exercise than pressing an LP and another reason that the range of titles available was limited. The process involved master, slave and transfer decks and the process to cut and individually wind tapes for final packaging. The process started with a master deck running a master tape. However, the master tape was not on a reel but stored in a tape reservoir similar to that on the Marconi-Stille recorder.

The master was spliced end to end to create a loop which would only be run forward. The master tapes were mostly duplicated direct from studio master tapes but sometimes they were created from an LP! The slave decks were loaded with blank tape 6000-8000 feet in length which was recorded and re-reeled onto a precision reusable reel. It was then mounted onto transfer machines that would wind the tape onto individual "consumer" reels that the operators would mount into the machine one-at-a-time. To add a modicum of automation to this process, there were pilot tones added to the bulk recorded tape which would signal the transfer deck to stop at the end of the recording. The machine would transfer the recorded tape until it encountered the pilot tones, then stop and back up until they were found again. The operator would then splice on a length of leader, splice a leader onto the start of the next recording, change the output reel and go again. These machines ran at very high speeds and used pneumatic disc brakes to stop the reels. The individual reel of tape was then labelled, boxed, and packed. A QC team would sample the duplicates on a random basis, listening to the entire tape to detect defects which would indicate problems with the slave recorders or transfer decks.

It’s no wonder that the cassette became the dominant tape format. Running an open reel duplication plant would have been a maintenance nightmare as well as being highly labour intensive. Cassette duplication, by contrast, was infinitely simpler.

The final nail in the coffin was the advent of the Walkman. Without any doubt, the cassette was the shizz and kicked off a personal music culture which eventually morphed into the iPod and then streaming audio via mobile phone. How many of us made our own mix tapes from our LP collection to listen to on the move either in a portable player or in the car?

These days, reel to reel hi-fi is very much a fringe pursuit and the cost of pre-recorded tapes either vintage or new duplicates prices and quality vary wildly. In addition to that, unlike a vintage vinyl record, tape degrades or “perishes” over time as the oxide and back coatings break down chemically. Even tapes stored in humidity controlled rooms suffer this fate. Tape restoration by baking is possible but this often results in a tape that can be played once or twice before the oxide layer breaks down terminally. Also, the longer a tape is stored, the greater the problem with print through. Add to this the inevitable problems with servicing complex machines that have been out of production for over twenty years and it’s obvious that it’s a pursuit for dedicated enthusiasts.

I haven’t dipped into the many other uses of magnetic media in this article. In truth, Ampex was developing tape recorders for video in parallel with audio machines. The technology developed to accurately and reliably record a big fat video signal was quite astounding with rotary heads and tape riding on a cushion of air to reduce wear and overall tape-path friction. Add to that the many uses of magnetic tape for data storage and its plain that those original AEG/BASF machines were massively significant to the development of computer technology as well as audio and video.