Punter

Active Member

- Joined

- Jul 19, 2022

- Messages

- 187

- Likes

- 1,011

Post WWII, it was discovered that the Germans had forwarded tape recording technology far beyond that in use by Allied countries, in fact wire recorders were the norm in the US and UK. The requisitioning (looting) of German radio stations provided equipment and recordings that would become the basis of tape recording technology in the US and the UK post war. Compared to the German technology, wire recording was crude and not suitable for high quality music recording. Tape recording would end up transforming the process of music recording. Prior to practical tape recorders, a musical performance would be transcribed onto a wax master which at most could accommodate around 4.5 minutes of audio. Tape recording facilitated the recording of longer, continuous performances and the ability to edit that material.

The superior technology of the Germans evolved into the first commercial tape machines made by Ampex in the USA. One of the pioneers of tape recording techniques was the great Les Paul who was given a two channel Ampex 200A by none other than Bing Crosby who had a financial interest in the Ampex company. Les, an inveterate experimenter, developed a range of tape recording techniques on that simple two track. Among his novel techniques were track bouncing, overdubbing, double-tracking, electronic echo and most importantly, multitracking.

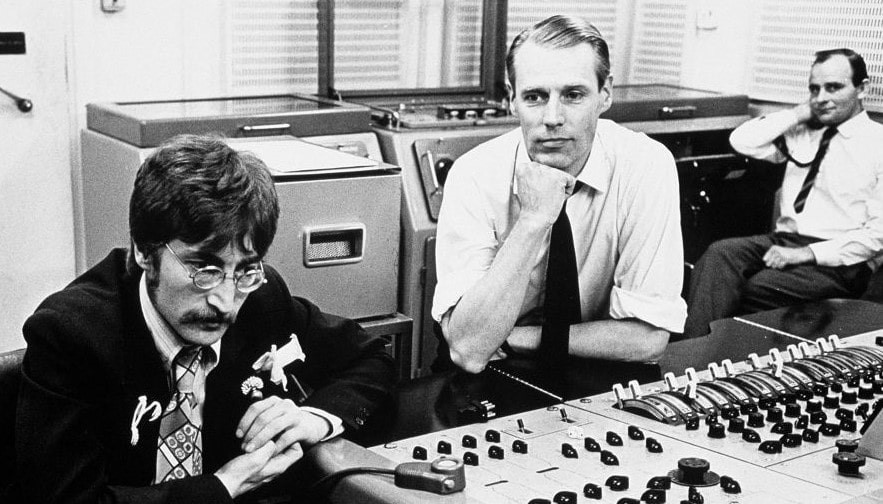

The utility of multitrack machines meant that they soon developed into 4 track, then 8. Dedicated multitrack tape machines transformed the way that music was recorded, edited and produced. Even using a relatively primitive four track recorder made by EMI, the Beatles and Engineer George Martin were able to create some of the most timeless and complex pop music ever made. A multitrack tape machine however was next to useless without a multichannel mixer and the two technologies evolved together from the famous REDD valve consoles at Abbey Road through to legendary units from Neve and SSL. In the 1960’s tape machines went from four track to eight track relatively quickly and topped out at 24 tracks on 2 inch tape by the end of the 80’s.

Using the techniques developed by Les Paul and the ever expanding capabilities of multichannel mixers, the live performance of music could now be broken into solo performances. Previously recorded tracks could be played back to a musician who was simultaneously recording a synchronised track to be added to the mix. Multiple takes could be stored on separate tracks so that the best could be chosen for the final mix. Outboard equipment for sound processing could be patched in to the audio chain. Studio environments could be changed to suit different instruments or to generate an acoustic effect that didn’t affect other elements of the recorded work. In fact it created an almost infinite array of creative possibilities which could enable artists and groups to achieve a unique “signature sound” in their produced work. This was a far cry from early forms of music recording which required a musician or group of musicians to play one take into a reversed megaphone connected to a transducer which transcribed their performance onto a wax drum and later a wax disk.

Another outcome from this rapid escalation of technology was the rise of the “Audio Engineer” and the Producer in the business of recording music. Unsurprisingly, some of the individuals engaged in this career became almost as well known as the artists they worked with. George Martin with the Beatles and (the now disgraced) Phil Spector for example. Engineers and Producers essentially became members of the bands they worked for. Furthermore, the production of music didn’t need to be limited to the original studio, multitrack tapes would be shipped off to be mixed at different facilities by a producer or engineer unconnected with the original session.

Music recording and production became a bona fide profession and within it, a whole pantheon of knowledge and techniques developed. Recording engineers and producers needed to know and understand the multitude of tape recording and audio mixing techniques but also an understanding of microphones and placement of same. An encyclopaedia could be written about all of the many facets of music recording and production (and I’m sure it has!).

At an equipment level, recording studios evolved into elaborate, purpose-built facilities and they themselves became famous, Abbey Road, Sun Studios and Capitol Studios to name a few.

If you were to sit at a classic recording console like a Neve VR36 for the first time, it might look very complex. However, a 36 track console, like the one pictured, has 36 copies of its input modules and then a “Master” module that is used to handle those sources. The Master module has facilities to switch, combine (group) channels, and direct signals coming from the input modules. A microphone signal could be switched to the input of the multitrack recorder or out to a processor and back onto a recorder track. Flexibility is the primary goal when it comes to this gear. Engineers also had to manage levels to avoid tape saturation and minimise generation loss when employing tape recorder techniques. Techniques like “track bouncing” can cause generation loss as it involves recording a mix of two or more tracks onto a target track, the purpose being to free up the source tracks so they could be reused.

All of this flexibility in the recording and mixing process meant that Engineers could basically create an audio soundscape from scratch, using all of the recorded elements and the almost infinite amount of creative potential in the mixing equipment. Using panning and phase effects, individually recorded elements can be placed anywhere in the psycho-acoustic space of a stereo image. This ability led to a flurry of effects created purely on the mixer, notably in the 70’s where there was a fashion for panning sources from left to right, sometimes rapidly which can be a very visceral experience if listened to on headphones! The acoustic space was often enhanced with various flavours of reverberation or echo created by feeding sources to outboard equipment like spring or plate reverb units. Even in the rare circumstance that a performance would be recorded with the entire group in the studio, the Engineer still had a great deal of influence over how the instruments and vocals were presented in the recorded stereo image. This is a typical “outboard rack”

Moving forward to the modern era, apart from some very high end studios and dedicated retro outfits, the days of consoles with acres of channel modules has pretty much run it’s course. In the current era, the equipment rollout is much more compact due to the whole process of recording, mixing and mastering being achieved in the digital domain. This has numerous advantages not the least of which is that the recorded material can be bounced around across the mix losslessly. No more juggling specific instruments on the multitrack, vocals on the middle tracks, drums on the outside. Also, the possibility of using all sorts of pre-recorded material available at the click of a mouse. If the analog multitrack studio had infinite possibilities, the digital multitrack studio expands on the concept of infinite! So the common elements in a modern digital studio is as follows.

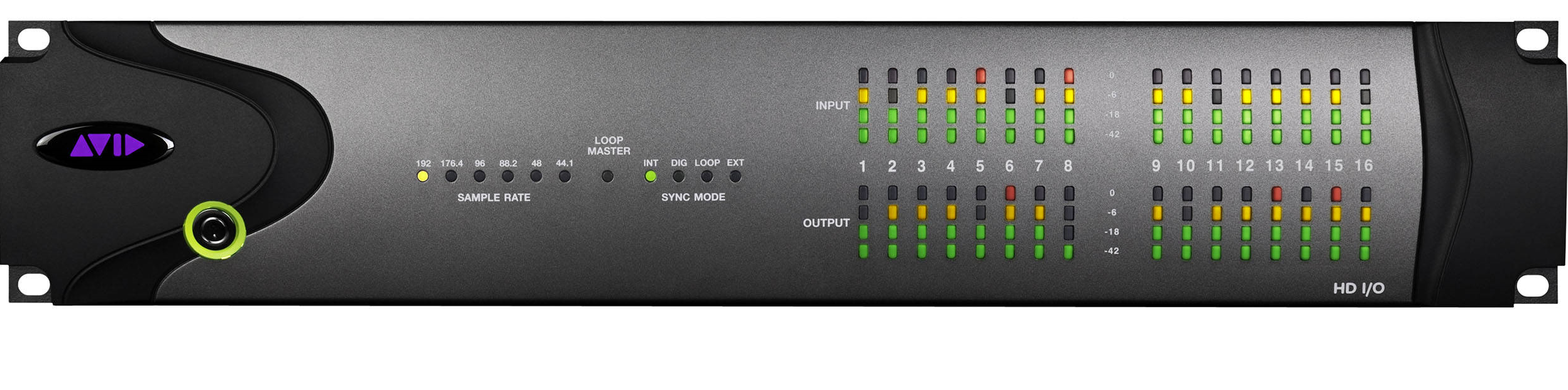

Analog to Digital interface (A/D).

The A/D is there to enable the recording of analog signals such as microphones and Direct Injection (DI) boxes to record instruments into the DAW (Digital Audio Workstation).

Digital Audio Workstation (DAW)

The DAW is generally a high spec computer which has the audio software installed on it. Running a decent multitrack session can be very resource hungry so these machines are usually loaded with CPU’s and memory to give plenty of computing headroom. Things get even more intense as plug-in effects and processing is added to the session.

From a software perspective, Avid ProTools is practically the industry standard.

Control Surface

While it’s possible to control every aspect of the recording process with a mouse and a keyboard, many engineers prefer to have a tactile device to control the mix. That’s where a control surface comes in, this is an Avid unit and quite common as it’s primarily designed to work with ProTools software, also an Avid product.

Effects and processing

In the tape era, processing was achieved using “outboard” equipment, that is separate processing units to cover reverb, compression etc. In the digital era, the outboard gear has all been replaced with “plug-ins” for the DAW software. There are so many of these it’s become an entire universe in itself but rest assured, you can do just about any effect digitally that you could do in analog and then some.

This just about rounds it out for the main differences in equipment from the multitrack tape age to the DAW age. The remaining studio equipment, microphones, DI’s, monitor speakers and other peripherals are all carried over.

While were talking equipment, one component that is often overlooked is the studio cabling. Any studio built in the 50’s onwards would have been wired up with kilometres of single channel, balanced twisted pair like Belden 8761 and later, the stereo version 8723. Belden and companies like them, designed cables to fit specific applications and developed the foil coated polymer shield which added to the noise rejection achieved with twisting the balanced pair along the length of the cable. The conductors would commonly be stranded #22AWG yielding a cross sectional area of around 0.32mm². The wiring from the studio to the control room would be on a large capacity multi-pair cable like Belden 1222 with #24AWG conductors. These cables would be terminated on XLR connectors in stage boxes in the studio and the various mics and instruments could be run to them on XLR cables. So basically, any sound you have ever heard on a recorded piece of music has arrived at the mixer on these types of cable even in a modern studio.

It never ceases to amuse me how “High End” HiFi cables, like RCA interconnects, have become so ridiculously over-built, when all of the sound you’re hearing through them has passed through many hundreds of metres of “ordinary” shielded pair cables in a studio. Moreover, cables that have been designed by real engineers to have noise rejection and shielding to a standard that even a low level microphone signal is not compromised.

Knowing what we now know about the process of music recording brings me to make this statement “The apparent “soundstage” of recorded, stereo music is an artificial psycho-acoustic space created by an Audio Engineer by mixing and processing multiple tracks”.

Yep, it’s fake. As a listener, you are hearing what the Engineer/Producer wants you to hear. The person behind the console has chosen the placement of the instruments, the type and form of the effects and the processing. The raw multitrack recording may have passed through several hands before being committed to a master which will then be a finished release.

Regardless of all the equipment in-between, the final sound you hear comes out of a pair of speakers (generally) and the whole process has been designed to create the best approximation of a stereo signal to present to the listener. Once again, it’s all an illusion, the truest form of stereo reproduction is from a binaural microphone pair and listened to on stereo headphones.

The superior technology of the Germans evolved into the first commercial tape machines made by Ampex in the USA. One of the pioneers of tape recording techniques was the great Les Paul who was given a two channel Ampex 200A by none other than Bing Crosby who had a financial interest in the Ampex company. Les, an inveterate experimenter, developed a range of tape recording techniques on that simple two track. Among his novel techniques were track bouncing, overdubbing, double-tracking, electronic echo and most importantly, multitracking.

The utility of multitrack machines meant that they soon developed into 4 track, then 8. Dedicated multitrack tape machines transformed the way that music was recorded, edited and produced. Even using a relatively primitive four track recorder made by EMI, the Beatles and Engineer George Martin were able to create some of the most timeless and complex pop music ever made. A multitrack tape machine however was next to useless without a multichannel mixer and the two technologies evolved together from the famous REDD valve consoles at Abbey Road through to legendary units from Neve and SSL. In the 1960’s tape machines went from four track to eight track relatively quickly and topped out at 24 tracks on 2 inch tape by the end of the 80’s.

Using the techniques developed by Les Paul and the ever expanding capabilities of multichannel mixers, the live performance of music could now be broken into solo performances. Previously recorded tracks could be played back to a musician who was simultaneously recording a synchronised track to be added to the mix. Multiple takes could be stored on separate tracks so that the best could be chosen for the final mix. Outboard equipment for sound processing could be patched in to the audio chain. Studio environments could be changed to suit different instruments or to generate an acoustic effect that didn’t affect other elements of the recorded work. In fact it created an almost infinite array of creative possibilities which could enable artists and groups to achieve a unique “signature sound” in their produced work. This was a far cry from early forms of music recording which required a musician or group of musicians to play one take into a reversed megaphone connected to a transducer which transcribed their performance onto a wax drum and later a wax disk.

Another outcome from this rapid escalation of technology was the rise of the “Audio Engineer” and the Producer in the business of recording music. Unsurprisingly, some of the individuals engaged in this career became almost as well known as the artists they worked with. George Martin with the Beatles and (the now disgraced) Phil Spector for example. Engineers and Producers essentially became members of the bands they worked for. Furthermore, the production of music didn’t need to be limited to the original studio, multitrack tapes would be shipped off to be mixed at different facilities by a producer or engineer unconnected with the original session.

Music recording and production became a bona fide profession and within it, a whole pantheon of knowledge and techniques developed. Recording engineers and producers needed to know and understand the multitude of tape recording and audio mixing techniques but also an understanding of microphones and placement of same. An encyclopaedia could be written about all of the many facets of music recording and production (and I’m sure it has!).

At an equipment level, recording studios evolved into elaborate, purpose-built facilities and they themselves became famous, Abbey Road, Sun Studios and Capitol Studios to name a few.

If you were to sit at a classic recording console like a Neve VR36 for the first time, it might look very complex. However, a 36 track console, like the one pictured, has 36 copies of its input modules and then a “Master” module that is used to handle those sources. The Master module has facilities to switch, combine (group) channels, and direct signals coming from the input modules. A microphone signal could be switched to the input of the multitrack recorder or out to a processor and back onto a recorder track. Flexibility is the primary goal when it comes to this gear. Engineers also had to manage levels to avoid tape saturation and minimise generation loss when employing tape recorder techniques. Techniques like “track bouncing” can cause generation loss as it involves recording a mix of two or more tracks onto a target track, the purpose being to free up the source tracks so they could be reused.

All of this flexibility in the recording and mixing process meant that Engineers could basically create an audio soundscape from scratch, using all of the recorded elements and the almost infinite amount of creative potential in the mixing equipment. Using panning and phase effects, individually recorded elements can be placed anywhere in the psycho-acoustic space of a stereo image. This ability led to a flurry of effects created purely on the mixer, notably in the 70’s where there was a fashion for panning sources from left to right, sometimes rapidly which can be a very visceral experience if listened to on headphones! The acoustic space was often enhanced with various flavours of reverberation or echo created by feeding sources to outboard equipment like spring or plate reverb units. Even in the rare circumstance that a performance would be recorded with the entire group in the studio, the Engineer still had a great deal of influence over how the instruments and vocals were presented in the recorded stereo image. This is a typical “outboard rack”

Moving forward to the modern era, apart from some very high end studios and dedicated retro outfits, the days of consoles with acres of channel modules has pretty much run it’s course. In the current era, the equipment rollout is much more compact due to the whole process of recording, mixing and mastering being achieved in the digital domain. This has numerous advantages not the least of which is that the recorded material can be bounced around across the mix losslessly. No more juggling specific instruments on the multitrack, vocals on the middle tracks, drums on the outside. Also, the possibility of using all sorts of pre-recorded material available at the click of a mouse. If the analog multitrack studio had infinite possibilities, the digital multitrack studio expands on the concept of infinite! So the common elements in a modern digital studio is as follows.

Analog to Digital interface (A/D).

The A/D is there to enable the recording of analog signals such as microphones and Direct Injection (DI) boxes to record instruments into the DAW (Digital Audio Workstation).

Digital Audio Workstation (DAW)

The DAW is generally a high spec computer which has the audio software installed on it. Running a decent multitrack session can be very resource hungry so these machines are usually loaded with CPU’s and memory to give plenty of computing headroom. Things get even more intense as plug-in effects and processing is added to the session.

From a software perspective, Avid ProTools is practically the industry standard.

Control Surface

While it’s possible to control every aspect of the recording process with a mouse and a keyboard, many engineers prefer to have a tactile device to control the mix. That’s where a control surface comes in, this is an Avid unit and quite common as it’s primarily designed to work with ProTools software, also an Avid product.

Effects and processing

In the tape era, processing was achieved using “outboard” equipment, that is separate processing units to cover reverb, compression etc. In the digital era, the outboard gear has all been replaced with “plug-ins” for the DAW software. There are so many of these it’s become an entire universe in itself but rest assured, you can do just about any effect digitally that you could do in analog and then some.

This just about rounds it out for the main differences in equipment from the multitrack tape age to the DAW age. The remaining studio equipment, microphones, DI’s, monitor speakers and other peripherals are all carried over.

While were talking equipment, one component that is often overlooked is the studio cabling. Any studio built in the 50’s onwards would have been wired up with kilometres of single channel, balanced twisted pair like Belden 8761 and later, the stereo version 8723. Belden and companies like them, designed cables to fit specific applications and developed the foil coated polymer shield which added to the noise rejection achieved with twisting the balanced pair along the length of the cable. The conductors would commonly be stranded #22AWG yielding a cross sectional area of around 0.32mm². The wiring from the studio to the control room would be on a large capacity multi-pair cable like Belden 1222 with #24AWG conductors. These cables would be terminated on XLR connectors in stage boxes in the studio and the various mics and instruments could be run to them on XLR cables. So basically, any sound you have ever heard on a recorded piece of music has arrived at the mixer on these types of cable even in a modern studio.

It never ceases to amuse me how “High End” HiFi cables, like RCA interconnects, have become so ridiculously over-built, when all of the sound you’re hearing through them has passed through many hundreds of metres of “ordinary” shielded pair cables in a studio. Moreover, cables that have been designed by real engineers to have noise rejection and shielding to a standard that even a low level microphone signal is not compromised.

Knowing what we now know about the process of music recording brings me to make this statement “The apparent “soundstage” of recorded, stereo music is an artificial psycho-acoustic space created by an Audio Engineer by mixing and processing multiple tracks”.

Yep, it’s fake. As a listener, you are hearing what the Engineer/Producer wants you to hear. The person behind the console has chosen the placement of the instruments, the type and form of the effects and the processing. The raw multitrack recording may have passed through several hands before being committed to a master which will then be a finished release.

Regardless of all the equipment in-between, the final sound you hear comes out of a pair of speakers (generally) and the whole process has been designed to create the best approximation of a stereo signal to present to the listener. Once again, it’s all an illusion, the truest form of stereo reproduction is from a binaural microphone pair and listened to on stereo headphones.